Kyle Sammin: Meet Pennsylvania’s new Congressional map — same as the old one

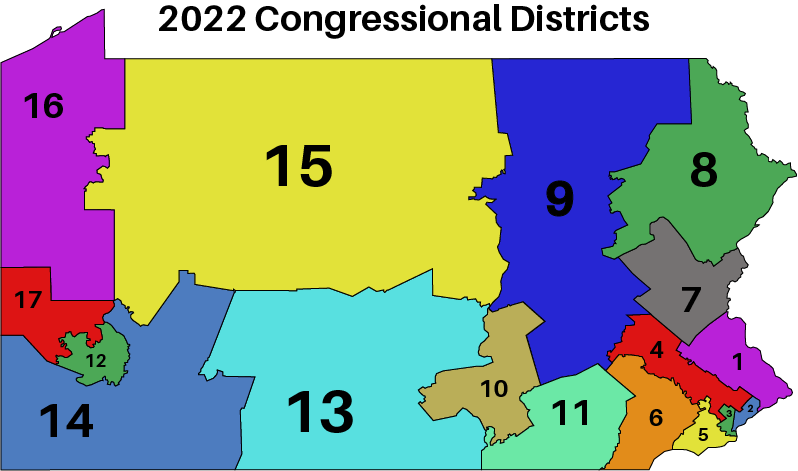

In a 4–3 decision late in February, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court chose a congressional map for the next decade. For the second straight time, the court chose to impose its vision, rather than that of the legislature or the governor.

Once again, the court (or four of its members, at least) seems to have lost its way, forgetting that the job of the judiciary is to say what the law is — not what they think it ought to be.

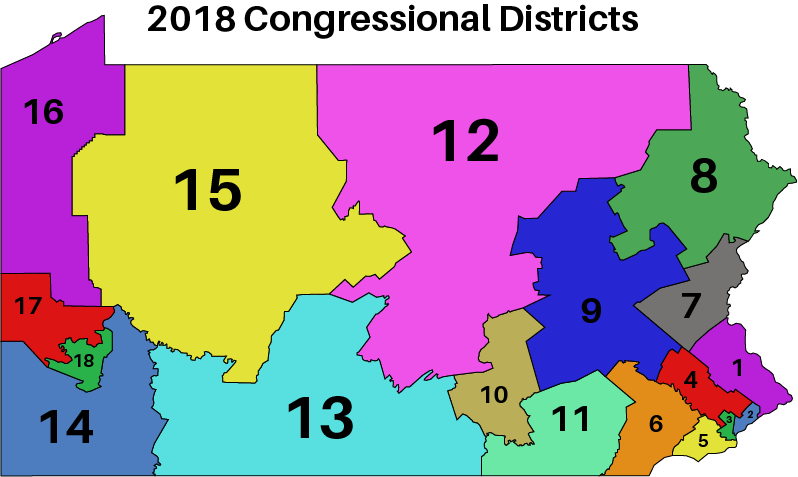

Heading into this round of redistricting, the state legislature knew that the ground had shifted. Having made a map themselves in 2011, legislators witnessed the state Supreme Court tear it up in 2018 in League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth. The court threw out the then seven-year-old map and ordered the legislature to make a new one within a few weeks, even before its own opinion describing how to do so was complete. When the legislature failed to make that happen, the Court drew its own map, which was used in the 2018 and 2020 elections. (For more on the history of this process, download Broad + Liberty’s white paper on redistricting, which I co-authored.)

READ MORE — Albert Eisenberg: Partisan redistricting won’t fix Dems’ PA advantage

This time around, things were supposed to get back to normal. The court had imposed some rules in 2018, but the process ostensibly still began and ended with the political branches. The legislature did pass a map in 2021, one that followed the often-conflicting guidelines of League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth, but Governor Wolf vetoed it. Wolf proposed his own, which also followed those guidelines. Neither was perfect, but that is the nature of divided government. Compromise happens after all other options are exhausted.

The state supreme court did not allow that process to happen. Instead, they looked at the map passed by the legislature and the version proposed by the governor and rejected both, choosing instead one submitted by the National Redistricting Action Fund, a non-profit organization affiliated with the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. Under the guise of being above partisanship, the court chose an avowedly partisan organization’s map, a plan from an outside special interest group that had the endorsement of neither Pennsylvania’s legislature nor its governor.

Neither [map] was perfect, but that is the nature of divided government. Compromise happens after all other options are exhausted.

As of press time, the court has not yet released the full opinion explaining its reasoning.

But we can venture an educated guess. Two factors stand out: the court’s majority (four Democrats) chose a map that favors their party. And the particular map they chose was one that hewed closest to its 2018 version.

That is to say, the biggest factor that set this map apart from all others was that it echoed the choices of the 2018 court, rather than those of the legislature or executive. The NRAF flattered the court with the idea that it knew better than the politicians — and it worked.

A look at the two maps below shows just how closely the court followed the old lines, especially in the areas where Democrats live. A more careful look shows a lot more sinuosity in the lines, creeping closer to the kind of gerrymandered maps produced this cycle by Democrats in Illinois, Maryland, and New York.

But even in copying the “non-partisan” map of 2018, the Democratic operatives at NRAF could not resist putting their thumbs on the scale and dragging out some of the old gerrymandering tricks.

Consider the district that includes Pittsburgh — the 18th under the old map, the 12th now. Nearly every district got bigger geographically, the result of going from eighteen districts to seventeen. But when the Democrats wanted to add territory to the new 12th district, which had been entirely within Allegheny County, they did not annex more of that county. Doing so would divide local jurisdictions less — which used to be a goal in district-drawing — but it would not help Democrats. So instead, they divided Westmoreland County and lumped in some of it with Pittsburgh. That way, the remaining Allegheny County suburbs could be used to make the 17th district less Republican.

The 5th district is, if anything, more egregious. Formerly consisting of Delaware County, Southwest Philadelphia, South Philadelphia, the revised 5th extends into Montgomery County. Not unreasonable: the old district already contained half of one township in MontCo (Lower Merion). But did the court add, say, the other half of Lower Merion to make up the difference? Of course not. They sent a tendril into Norristown to pull Montgomery County’s seat into a different district than the rest of the county. The new lines are quite obviously less compact, and split more jurisdictions.

Perhaps the most ridiculous change comes in the neighboring 4th district, centered on Montgomery County. As noted already, the Democrats’ maps stripped out the county seat from the county, and a few townships were lost to the 1st district for population equality reasons. But then to make it up, the designers stretched the 4th deep into Berks County, completing the dismemberment of that jurisdiction.

The new 4th district has more carve-outs than a Thanksgiving turkey and stretches from the Philadelphia border to the heart of Berks County farm country. The old fourth district was not exactly compact — it had a Reock compactness score of 32 (scale of zero to 100, with 100 being the most compact, zero the least). But insofar as it was non-compact, it was because Montgomery County is longer than it is wide, so at least it was keeping a community intact. The 2022 version has a Reock score of zero and fails to even keep the county together.

We could examine each of the seventeen districts and find similar complaints. Every map-drawing exercise requires choices, and each choice the court made here favored Democrats, starting with the biggest choice of all, using the politically slanted lines from 2018 as a starting point. But even beyond that, each deviation from the old map was made with the interests of Democratic officeholders in mind.

For Pennsylvanians, the next decade of Congressional elections may look much like the last: court-ordered lines to protect Democratic incumbents.

Kyle Sammin is Broad + Liberty’s Editor-at-Large, co-host of the Conservative Minds podcast, and a resident of Montgomery County. @KyleSammin