Thom Nickels: Owen Wister and the ‘Western Cure’

Several years ago while researching my book, Literary Philadelphia: A History of Poetry & Prose in the City of Brotherly Love, I looked into the life of Owen Wister, the author of the western novel, The Virginian.

Wister was the only child of a physician father and an actress mother who herself happened to be the daughter of English actress, Fanny Kemble. The Wister family had strong Philadelphia patrician roots. As an only child, young Wister was sent to exclusive boarding schools in New England and Switzerland.

He entered Harvard in 1878, where he achieved top honors in musical composition and dramatic writing. Perhaps it was his success in writing the libretto for Hasty Pudding’s comic opera, Dido and Aeneas, that made him want to become a composer.

He wanted to go to Paris and write music in a garret but in order to do that he needed his father’s approval and financial support. Starving in Paris without financial support from home was not an option for Wister, despite the fact that many expatriate American artists went to Paris on a shoestring budget. When the almost penniless Ernest Hemingway went to Paris, for instance, he survived by killing and roasting the pigeons he caught outside his window.

Wister’s mother had heavy artistic leanings (she was a magazine writer), but his father was a practical man and not keen at all on his son’s ambition to study musical composition in The City of Light — a grounded family physician, he wanted his son to enter an equally grounded profession. Yet in the end, he gave his consent, and even provided his son with the financial support he needed.

Now there was nothing standing in the way of Wister becoming a great composer. He had only to start building from scratch and start a legacy as great as Chopin’s — provided, of course, that he could turn his dream into reality. For most artists, achievements like this rarely occur in a straight, unencumbered path without crooked detours and unexpected pitfalls.

Samuel Butler’s famous saying, “Thus do we build castles in the air when flushed with wine and conquest,” certainly applied to Wister because his Parisian musical ambitions eventually hit rock bottom. In 1883, he returned to Philadelphia after resigning himself to the idea that he was no Chopin and that he had best become … a Philadelphia lawyer.

So he returned to his father’s home and took a junior position in a law firm, something that for many young men would have been a fine solution, although in Wister’s case it led to intense dissatisfaction, restlessness and stress.

While working at the law firm, he tried his hand at another artistic endeavor, co-authoring a novel with a friend. But then, just as he was about to enter Harvard Law School, his interior world fell apart.

Psychoanalytical experts say he had a nervous breakdown, meaning that he also suffered from vertigo, paranoia, blinding headaches and hallucinations.

His father, understandably alarmed, urged him to come home at once, so the much weakened Wister complied, although he had now developed Bell’s palsy, often described as a paralysis of one side of the face, causing it to droop. Bell’s palsy can happen overnight and it can last several weeks.

The numbers of poets, novelists and artists who have had nervous breakdowns are legion. Many have sought refuge in hideaways, sanatoriums, and warm climates after coming apart internally.

In Philadelphia, Wister consulted Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a member of the Franklin Inn Club during the Inn’s golden era. (The Franklin Inn Club on Camac Street still flourishes today, however it is no longer a literary club where members have to be published authors — it is more of a dinner and discussion club for strict, woke, liberal Democrats).

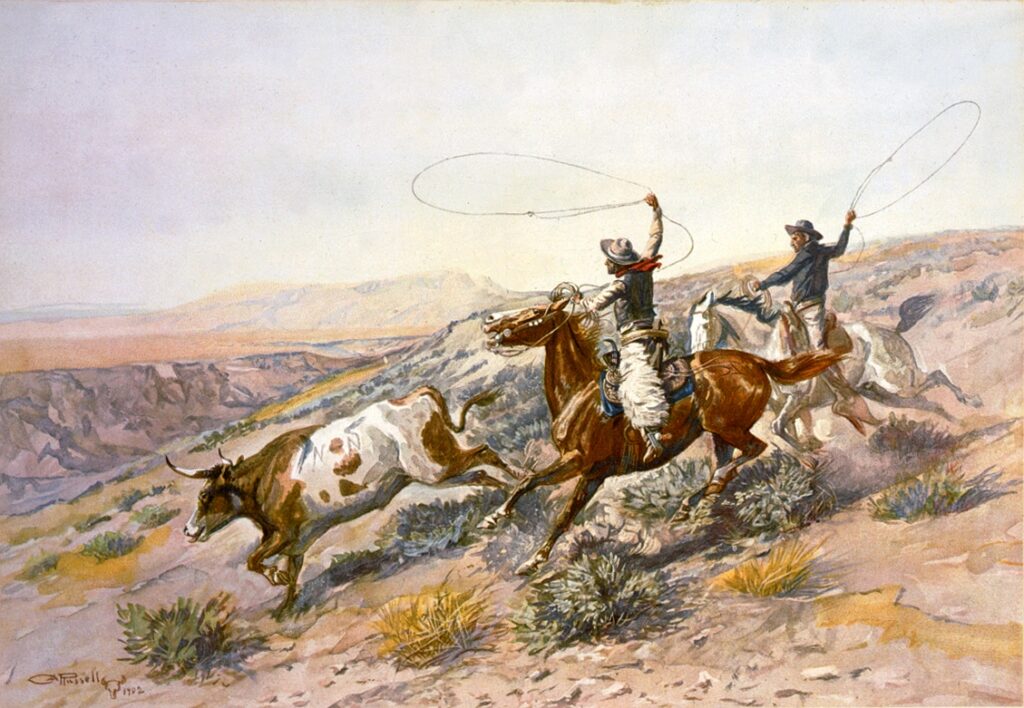

Mitchell diagnosed Wister with a severe case of neurasthenia and suggested a trip to a Wyoming ranch. Mitchell had developed a system for treating nervous men, and that was to send them to the west where they could rope cattle, hunt, ride horses, and engage in male bonding rituals. In his 1871 book, Wear and Tear: Or Hints for the Overworked, Mitchell encouraged nervous men to go west in order to reinforce their masculinity and to test their willpower.

“Under great nervous stress,” Mitchell wrote, “The strong man becomes like the average woman.”

Had Wister been born today, his attending physician would never have suggested that he travel west for his health, as was the custom of the day, but would put him on a regime of psychotropic meds that would have deadened his energy and creative talents like T.S. Eliot’s “a patient etherized upon a table.”

Weir Mitchell’s “go West” cure for men was a staple of 19th-century life. For Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins, who was fired from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts for removing the loincloth of a male model in front of female students (and who was then ostracized by Philadelphia society,) going west was more than rehabilitative. It saved his life.

“For some days I have been quite cast down, being cut deliberately on the street by those who have every occasion to know me.” Eakins wrote in a letter to his sister.

Eakins sought his western cure in the Dakotas and when he returned he was “built up miraculously,” according to poet Walt Whitman.

Whitman himself sought his own western cure in 1879 and documented that journey in Specimen Days (1882).

Even “Rough Rider” Teddy Roosevelt returned from his western cure without what his detractors called his “former effeminate looks” and “high voice that often provided comparison to Oscar Wilde.”

These were different times, indeed.

After three weeks in Wyoming herding cattle, wrestling steer, riding horses, swimming and bathing nude in icy outdoor creeks, and sleeping outdoors in a tent, Wister felt like a new man. “I am beginning to be able to feel I’m something of an animal and not a stinking brain alone,” he wrote to Dr. White..

Dr. Mitchell also had his prescribed “rest cures” for women.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who wrote about Mitchell in The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) was once a patient of his but the treatment was quite different for females. Instead of open skies, camp fires at night and swims in local creeks, nervous women were encouraged to seek seclusion, were overfed, and received massage treatments and electrotherapy.

Although historians have come to categorize Mitchell’s rest cure therapy as nothing more than nineteenth-century misogyny, Wister was so entranced by the beauty he experienced in Wyoming that he came to idolize the cowboy, which in turn would form the basis for his classic novel, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, about a Wyoming cattleman that would go on to become one of the country’s first mass market bestsellers.

In his book, “The History of Men: Essays on the History of American and British Masculinities,” Michael S. Kimmel writes, “To Wister, the west was ‘manly, egalitarian, self reliant, and Aryan’ — it was the true America, far from the feminizing, immigrant infected cities, where… masculine women devoured white men’s chances to demonstrate manhood.”

Wister never forgot his ranch experience out west, and would spend the next fifteen years traveling to Wyoming during the summer months, visiting ranches, cow camps, and remote cavalry outposts while getting to know the gamblers and ranch hands. These sojourns provided him with stories that he began publishing in Harper’ Weekly.

He started work on The Virginian, and its publication in 1902 changed his life forever. The book sold 200,000 copies in one year and was adapted for Broadway, and went on to be the basis for five movies, and a television series.

The book provided the general outline for the classic western novel. The stock characters included: the green, naïve east coast narrator; the local virginal schoolmarm; the mean, savage Indian; the tobacco chewing cattle rustler; the wise camp cook who solved problems; the inexperienced, shy, callow kid; and the dreaded “white man” villain.

Since its publication, The Virginian has never been out of print, despite the character stereotypes mentioned above.

It didn’t take long for Wister to become more famous than his friend, novelist Henry James, whom Wister revered and thought of as “a real novelist.” In a curious twist of fate, the recognition that he had sought for his musical compositions in Paris was now not only his but in triplicate, yet fame made him decidedly unhappy because he looked on his fans as “the semi-literate public.” He wanted Henry James’s fan base, not “the repugnant masses” who he regarded as unread and uneducated.

After writing and publishing The Virginian, Wister was never totally happy with east coast cities, especially Philadelphia.

He complained of Philadelphia’s “rabble of excessive democracy, populist politicians, unassimilated immigrants and tourists.”

Unassimilated immigrants: did he really say that? In Philadelphia he tried to make a decent life for himself by dabbling in many things, including politics, writing non-fiction like the story of his friendship with Teddy Roosevelt, Roosevelt: The Story of a Friendship.

In his book, Romney, Wister compares the aristocracy of Boston and Philadelphia, finding in Boston a Puritan zeal for achievement and civic service but in Philadelphia a Quaker preference for toleration and moderation that often leads to acquiescence and stagnation. (Hidden message: Try not to be a Quaker).

His journals and letters, edited by Frances Kimble Wister, were published in 1958.

Thom Nickels is a Philadelphia-based journalist/columnist and the 2005 recipient of the AIA Lewis Mumford Award for Architectural Journalism. He writes for City Journal, New York, and Frontpage Magazine. Thom Nickels is the author of fifteen books, including “Literary Philadelphia” and ”From Mother Divine to the Corner Swami: Religious Cults in Philadelphia.” His latest is “Death in Philadelphia: The Murder of Kimberly Ernest.” He is currently at work on “The Last Romanian Princess and Her World Legacy,” about the life of Princess Ileana of Romania.

This is an extremely interesting article – thank you. I plan to inquire about your books at the library. Thanks for sharing.

Great article, thank you. I will re-read “The Virginian.”

Would staging the play of it be successful now, as our nation returns to a cultural normalcy lost these last four years?

Do I recall correctly that it was Wister’s friendship with Frederick Remington that led to the placement of Remington’s bronze, “The Cowboy” on that rock ledge in Fairmount Park, after a search for a dramatic location?

Excellent article. I’ll be reading these works cited. Thank you!