Farthest North for the Stars and Stripes

It was shortly after 2 pm on August 10, 1884, and just outside the home of Margaret Linn on Lombard Street in Philadelphia a crowd of thousands had gathered. They solemnly watched as a flag-draped coffin was brought out and placed on a horse-drawn hearse. Soldiers and veterans lined both sides of the street and as the long procession passed between their ranks, they saluted the coffin that held the body of Mrs. Linn’s son, Sergeant David Linn of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry.

The procession route covered over four miles before finally arriving at the Mount Moriah cemetery burial site in Southwest Philadelphia. A silence fell among the crowd as the coffin was lowered into the grave. As reported in the Philadelphia Times, Post 5 Commander R.C. Purvis “spoke in quiet tones of the brave volunteer whose memory they had assembled to honor; a comrade who had willingly given his life in a glorious effort to serve his country in an important and perilous undertaking. As Commander Purvis ceased speaking, the crowd moved back. Lieutenant Truman’s squad fired over the grave a parting salute of three charges and Sergeant Linn’s second funeral was at an end.”

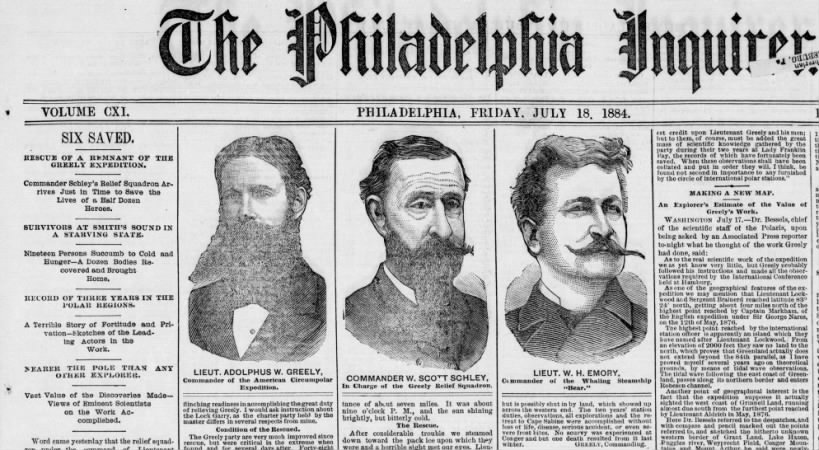

This year marks the 140th anniversary of the rescue of the survivors of the ambitious, but ultimately tragic, Lady Franklin Bay Expedition to the North Pole. Commanded by Civil War veteran First Lieutenant Adolphus Greely, and more commonly referred to as the Greely Polar Expedition, the scientific voyage was launched in 1881 under the auspices of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The expedition’s primary goal was the establishment of a scientific station at Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic where it would collect meteorological, astronomical, and magnetic data as part of the First International Polar Year. Additionally, the still relatively young United States wanted to gain prestige among the powerful European nations and hoped that Greely and his crew would exceed Britain’s long-held polar record of “Farthest North” and claim that title for America.

The initial 22 members of the expedition, which included Philadelphians Sergeant David Linn and Sergeant Hampden Gardiner, departed St. Johns, Newfoundland on July 7, 1881, aboard the U.S.S. Proteus and later stopped at Greenland to pick up Dr. Octave Pavy and two Eskimo guides, Jens Edward and Thorlip Christiansen. The Proteus then steamed to Ellesmere Island where it safely arrived at the mouth of Lady Franklin Bay on August 11, 1881. Over 300 tons of supplies, supposedly enough to last three years, were then offloaded and the men immediately commenced construction of a shelter they named Fort Conger. When the Proteus departed the expedition on August 26, 1881, to return to Canada, the men could not have possibly known the terrible fate that awaited them in the years ahead.

Their first year at Fort Conger was largely successful, with the collection of valuable scientific data and numerous explorations to the interior of Ellesmere Island. The highlight of the expedition occurred on May 13, 1882, when three members of the party, Lt. James Lockwood, Sgt. David Brainard, and Thorlip Christiansen, reached 83 degrees 23 minutes 8 seconds North to claim the prestigious title of “Farthest North” for the United States. The euphoria of that moment is chronicled in Buddy Levy’s excellent book on the Greely expedition, Labyrinth of Ice: “Brainard, nearly delirious with fatigue and hunger, was giddy: ‘We unfurled the glorious Stars and Stripes to the exhilarating northern breezes with an exultation impossible to describe….’”

Unfortunately, uplifting moments like this would soon fade into memory. A series of misfortunes over the next two years relentlessly plagued the men as the expedition gradually descended into a grim battle for survival. A resupply ship with food, provisions, and letters from home was expected to arrive at Fort Conger in July 1882, but thick pack ice prevented it from reaching Lady Franklin Bay. The ship was forced to turn around and left some of the supplies at Cabe Sabine and Littleton Island, 250 miles south of Greely and his crew.

The men gradually realized that there would be no resupply ship and they would have to survive the next year with what they had. Battered by snowstorms, sub-zero temperatures, months of polar darkness, and morale-crushing isolation, the crew bravely tried to make the best of their predicament and continued with their scientific experiments and data gathering.

A June 1883 rescue effort led by Lieutenant Ernest Garlington aboard the USS Proteus failed when the ship was crushed by ice and sank in Smith Sound, its crew lucky to survive.

By August 1883, Greely and his men concluded that the rescue effort must have also failed, and Greely then enacted a previously devised plan to leave Fort Conger in their few small boats with minimal provisions in an attempt to reach the supplies at Cape Sabine. In September 1883, their small escape boats became trapped in ice, and they were forced to transfer to a large floating ice floe where they would be at the mercy of the chaotic sea’s shifting tides and currents.

By October, the ice floe eventually drifted to Eskimo Point, just south of Cape Sabine. The relieved men departed the floe and immediately went to work on the construction of a winter shelter. Two of them set out for Cape Sabine to determine if there were any supplies. They returned to Eskimo Point with written records of the failed relief expeditions of 1882 and 1883, as well as the locations of additional supplies. Greely then decided to relocate his team 20 miles north of Cape Sabine in a makeshift camp. Although the supply caches were eventually retrieved, they were not enough to sustain Greely’s crew for long.

The polar winter of 1883-1884 was particularly cruel for Greely and his crew as each day became a battle for survival. With a dwindling food supply, the men resorted to eating seal skin carved off their clothing and boots, as well as seaweed and candle wax. On January 18, 1884, Sergeant William Cross died from malnutrition and scurvy, the first member of the expedition to die. Over the next several months, sixteen more would succumb to starvation, disease, hypothermia, or drowning. Private Charles Henry was shot and killed for stealing from the meager remaining shrimp rations. Philadelphians Sergeant David Linn and Sergeant Hampden Gardiner died on April 5, 1884, and June 12, 1884, respectively. Most of the dead were buried in hastily dug shallow graves due to the dire conditions.

During that winter, and unbeknownst to Greely and his crew, the United States Navy organized a rescue expedition led by Commander Winfield S. Schley, later a hero of the Spanish-American War. Schley’s squadron consisted of 110 Navy officers and sailors and four ships: the USS Bear, the USS Thetis, the HMS Alert (a loan from the British in appreciation for America’s help in recovering the HMS Resolute), and the Loch Garry, a floating coal depot for the rescue ships.

A rescue party from Schley’s expedition miraculously managed to reach the seven emaciated survivors on June 22,1884: Lieutenant Greely, Sergeant David Brainard, Corporal Joseph Ellison, Private Henry Bierderbick, Private Maurice Connell, Private Julius Frederick, and Private Francis Long. The bodies of the dead that could be located were also retrieved and transported to the rescue ships. Unfortunately, Corporal Ellison’s legs had to be amputated due to frostbite and he subsequently died during the voyage home.

When they finally arrived back in the United States the survivors were initially hailed as heroes, but subsequent forensic examinations of the dead bodies later led to accusations of cannibalism. The survivors countered that it wasn’t true and that the flesh of the dead had been cut from their corpses and used as fish bait. Sergeant Brainard told a reporter, “I know nothing of cannibalism.”

The accusations eventually faded. Additionally, a military inquiry into the shooting of Private Henry concluded that it was justified.

The survivors of the expedition gradually blended back into society. Lt. Adolfus Greely remained in the Army and served as the Chief Signal Officer during the Spanish-American War. He retired as a Major General in 1908 and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1935 on his 95th birthday via a special Act of Congress. Greely died in 1935 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, not far from his old friend and fellow explorer Sgt. David Brainard.

The scientific data gathered by the Greely expedition is still utilized to this day and chronicled in Levy’s Labyrinth of Ice: “Greely’s work has been vital and far reaching, its legacy seen in nearly one hundred polar research stations…that exist in the world today. The knowledge gained and practices employed by Greely have also benefited teams training for and conducting lengthy tours on space flights and living on manned space stations.”

As I recently walked among the graves at Mount Moriah cemetery while searching for Sgt. David Linn’s headstone, I couldn’t help but notice the large number of veterans buried there. A few of them had given their lives in war. And it is my sincere hope that as we commemorate Memorial Day in 2024, we not only honor and remember those service men and women who gave their lives while battling an enemy for the preservation of freedom, but also those who died while battling the elements in the pursuit of knowledge and discovery.

Chris Gibbons is a Philadelphia-area writer. His recent book, “Soldiers, Space, and Stories of Life’” available at Amazon, features numerous stories about the harrowing experiences of America’s war veterans

Once again writer Chris Gibbons manages to capture the heroic moments of so many worthy soldiers and researchers in his articles and stories. His attention to detail is always shining through in his work and I will continue to look for his next gem of storytelling.

Jim Marino