Chris Gibbons: Invisible wounds that kill

“Poor is the nation that has no heroes, but poorer still is the nation that having heroes, fails to remember and honor them.”

—Cicero

I stood in the Har Nebo Cemetery on Oxford Avenue in Philadelphia and looked out at the gravestones that surrounded me. The high autumn lawn of the cemetery undulated like an ocean in the wind, green grass waves breaking over tombstone shores. I was heading to the section for indigent Jews, searching for the gravesite of a World War II veteran. Although I’d never met him, I felt I had to come and pay my respects.

I found his grave, marked only by a four-square-inch plaque that bore his name, and knelt down beside it. I planted a small American flag and said a short prayer. The silence of the moment was only broken by the sound of the American flag as it whipped in the wind.

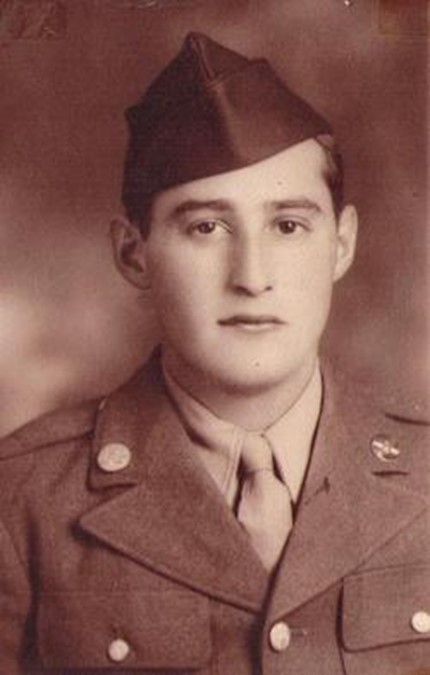

Marvin Ravinsky grew up in a tough Jewish section of North Philadelphia. He enlisted in the Army in 1943 and fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific Theater. He was at Okinawa, where psychiatric combat stress among American soldiers was an unbelievable 48 percent, as over 26,000 U.S. soldiers had to be removed from the battlefield because of “battle fatigue.”

During the fighting, Marvin and some other soldiers were trapped in a cave by the Japanese. They riddled the cave with bullets, killing everyone but Marvin. The Japanese entered the cave and began bayoneting the bodies. They were using the tactic to find and kill any survivors. Marvin played dead, and through his sheer will to live, didn’t move or cry out when a Japanese bayonet pierced his thigh. Bleeding profusely, Marvin waited until they left the cave, and then crawled out from under the lifeless bodies of his friends.

Marvin returned home with a Purple Heart medal awarded for his injuries, but there was no recognition for the hidden wounds that eventually infected his mind. He fought a long, losing battle with the demons of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), as there was little government help given to the traumatized veterans of WWII. These men and their families were left to deal with the nightmares and debilitating effects of this affliction on their own.

Unfortunately, Marvin slowly spiraled into the dark abyss of PTSD and eventually lost himself and his family. In his later years, he was destitute and was taken advantage of by drug addicts in his neighborhood until he was rescued by social workers. He died of lung cancer on Aug. 12, 2008.

I never knew Marvin Ravinsky. His cousin was going through his personal belongings and among his medals and other WWII memorabilia she found a copy of an article I wrote in which I stressed the need to honor the WWII veterans who fought in the Pacific. Since I was a child, soldiers have always been my heroes, and to know that one of them kept my article among the things he cherished the most was touching.

READ MORE — Chris Gibbons: Echoes of heroes

On this Fourth of July, remember all of those Americans throughout our history who helped preserve our freedom and independence, especially those who gave their lives. Remember that although some were killed on the field of battle, others, like Marvin Ravinsky, eventually succumbed to the hidden wounds of war — wounds that couldn’t be seen, yet were fatal nonetheless. Marvin died a slow death that began the day he first witnessed the horrors of battle as a young soldier, and finally ended over 60 years later in the cold hospital bed of a lonely, disoriented, and forgotten old man.

It doesn’t seem fair. Heroes aren’t supposed to die this way.

As I stood above his grave, I wished there was something more I could do to honor Marvin. I felt so helpless. How sad, I thought, that we live in a world in which we praise people for acting in a movie, or putting a ball through a hoop, or singing songs on a stage. We misuse terms such as “great” and “courageous” when describing them, but conveniently forget the people who fought for this country and who are much more deserving of these accolades. I can just hear the neighborhood junkies: “He was just some old, crazy Jew. Who cares?”

I turned to leave, but was compelled to carry out one final gesture that seemed somewhat clichéd, yet very appropriate. As I faced his grave one last time, I straightened my back and saluted. The wind howled in sorrow, and the green grass waves lapped at my feet as the American flag whipped above the grave of Marvin Ravinsky.

AFTERWORD

The article Marvin’s cousin found when sorting through Marvin’s belongings shortly after he died was one I had written about my childhood neighbor, WWII veteran Jack Kerwood (“The Scars of War”). To say that I was deeply moved upon hearing this from Marvin’s cousin would be an understatement, and I was once again reminded of the power of the written word. But perhaps the greatest satisfaction I received from writing this essay occurred some five months after it was published when I received an e-mail that read in part:

“My mother just forwarded me the article you wrote about Marvin Ravinsky. He was my Grandfather. I never knew him. I wanted to thank you for giving me a little bit of insight into Marvin and my family history. I am proud to know that my Grandfather was a hero… Life is short; so those of us who are still living should do our best to honor those who have passed on. We should especially remember our heroes. Thanks again.”

Chris Gibbons is a Philadelphia writer. His book, “Soldiers, Space, and Stories of Life,” a compilation of 78 of his essays — including this one — is available on Amazon.

Thank you Chris Gibbons for yet another great article about our history and soldiers. This article is thought provoking, informative and interesting. I was deeply touched by the personal story of Marvin Ravinsky a true American hero!

My book The Hidden Legacy of World War II about my WWII paratrooper father whose undiagnosed PTSD devastated our family tells the unknown story of so many veterans of that war who didn’t receive help. Even though my dad was written about in books and portrayed by Richard Beymer in The Longest Day, it wasn’t until he was 80 that his war trauma was recognized by the VA.