Chris Gibbons: This Memorial Day, remember the Meuse-Argonne

“No two men came out of the Meuse-Argonne exactly the same. Some changed their political outlook. Some grew more idealistic or embittered. Some found God; others lost their faith. All, however, had changed. The country would never be the same.” (Excerpt from “To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne 1918” by Edward G. Lengel)

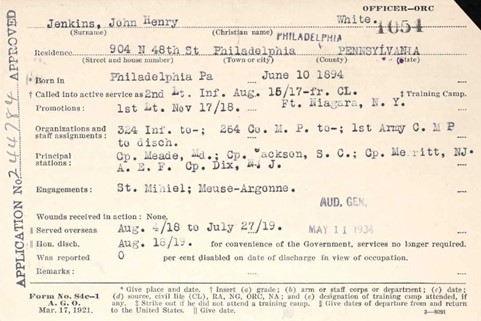

When I found the World War I Service and Compensation File of 1st Lieutenant John H. Jenkins, I immediately looked at the document’s “Engagements” section. I often do that now when reviewing these files because this section lists the battles in which a veteran fought, which will give me an idea of what he may have endured.

There are two words I often find in this section that always give me pause. I pause because I’ve read extensively about what happened there and I try to imagine the Hell endured by those who fought there. I also pause out of respect.

On this day, my search for the alumni of Roman Catholic High School who fought in the Great War led me to John Henry Jenkins of the class of 1912. I not only wondered what happened to him during the war, but in his post-war years as well, and, again, I paused to stare at the two words I’ve come to know all too well: Meuse-Argonne.

READ MORE — Chris Gibbons: A prayer for the Unknown Soldier

. . .

The Battle of the Meuse-Argonne in World War I is the largest and deadliest battle ever fought by American soldiers.

The bitterly fought 1918 offensive, the main thrust of which was between France’s Meuse River and Argonne Forest, lasted 47 days, from Sept. 26 to Nov. 11. Nearly 1.2 million American soldiers participated in the battle, and when it concluded, the US had suffered an astounding 122,000 casualties, with 26,277 U.S. troops dead and over 95,000 wounded.

As Edward Lengel accurately wrote, America would never be the same after the Meuse-Argonne, and I would come to learn that those who fought there were never the same as well.

U.S. veterans of the Meuse-Argonne returned to a country that was ill-equipped to deal with the psychological trauma that would haunt many of them in their post-war years. PTSD was referred to as “shell-shock” in the WWI era, and veterans suffering from its debilitating effects were largely ignored by the medical community and by society in general, resulting in rampant unemployment, alcohol abuse, and suicide.

In “To Conquer Hell,” Edward Lengel recounts the all-too-common story of Meuse-Argonne veteran Reese Russell who returned home to Cedar Bluff, Virginia a broken man.

“He never spoke of what he had seen in France, and forbade his family to mention the war in his presence… Russell began drinking as soon as he returned home. He drank through the economic recession of 1919… He drank through the Great Depression… In 1941 America entered the Second World War, and Russell drank even more, as if in sympathy for the GIs about to die, or in realization that his war — the so-called ‘War to End All Wars’ — had been fought in vain. And he never slept. He went through the motions … but he never closed his eyes in sleep, “unless,” his daughter recalled, “one could call the stupor he fell into when he drank in his later years sleep.” Perhaps he feared his dreams would take him back to the war. He died a broken man at age 61. As his daughter heard taps played over his lonely country grave, a sense of relief enveloped her. At last, her father’s torments had ended, and he could sleep.”

It was not only the common foot soldier who was haunted by the Meuse-Argonne. Major Charles Whittlesey gained notoriety as the heroic commander of the 77th Division’s famed “Lost Battalion.” Surrounded and vastly outnumbered by German soldiers in the Argonne Forest during the great battle, Whittlesey and his men courageously held on and refused to surrender. The fight eventually went hand-to-hand. Their plight was front-page news in the US.

Whittlesey was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions, but he was continually plagued by the horrific memories of the battle. He had recurring nightmares of the screaming wounded, and once had a disturbing dream in which a young soldier’s “cold in death face” touched his own.

Whittlesey was an honorary pallbearer, along with the equally famous Sgt. Alvin C. York, for the first ceremony honoring America’s Unknown Soldier at Arlington in 1921. A distraught Whittlesey told a friend he thought the Unknown Soldier might be one of his own men and said, “I wish that I had not come here.”

A few days after that ceremony, Whittlesey jumped to his death from the deck of the S.S. Toloa while en route to Cuba.

Philadelphia’s Roman Catholic High School had over 1,500 alumni serve in World War I. Thirty-four of them gave their lives. My ongoing search for the names of the fallen has resulted in the discovery of nineteen names thus far, and I’ve learned that the majority of those who lost their lives in battle died in the Meuse-Argonne.

. . .

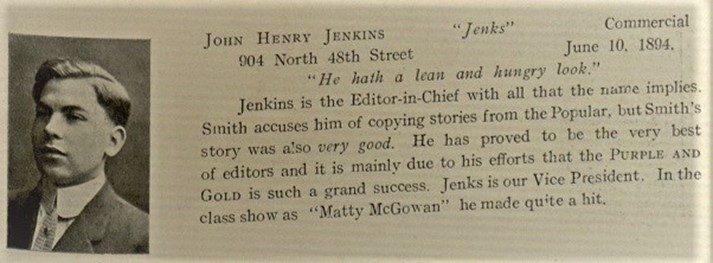

During his senior year at Roman, John H. Jenkins, nicknamed “Jenks,” had a bright future ahead of him. He was the class Vice President and was Editor-in-Chief of both the yearbook and school newspaper, called The Purple and Gold. Roman’s records revealed that Jenkins was also an actor in the school play, “The College Widow.”

Following graduation from Roman, he attended the University of Pennsylvania and was scheduled to graduate in 1918, but the cloud of war dimmed his plans. Just one month after the US declared war on Germany in April 1917, Jenkins enlisted in the army. Three months later he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant while serving in the 79th Division.

He arrived in France in Aug. 1918 and just one month later his 1st Army Corp. fought at the Battle of St. Mihiel, the first large offensive launched by the United States in the war. Two weeks after St. Mihiel, John Jenkins would experience the horrors of the Meuse-Argonne. Six days after the battle ended, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

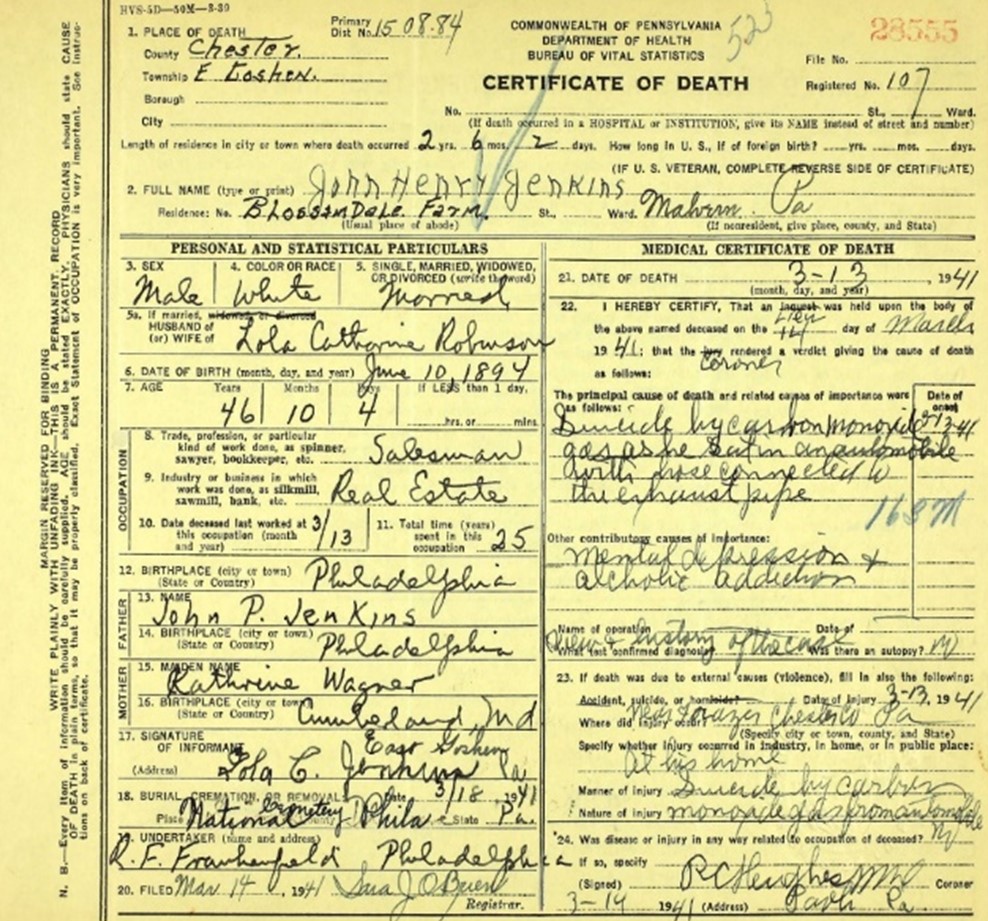

I don’t know exactly what Jenkins experienced at the Meuse-Argonne or how it impacted his life after the war. I can only surmise. I did learn that upon returning home he received a B.S. in economics from Penn and became a real estate salesman, but not much more than that. I’ve tried to track down his relatives for information, but to no avail. Jenkins and his wife, Lola, never had children. His only sibling, Henrietta, married late in her life and died in 1974. Her husband died in 1981 and he had two children from a previous marriage, but he and Henrietta never had any children of their own.

On March 13, 1941, while at his home in Malvern, Pennsylvania, John Henry Jenkins, age 46, took a hose and connected one end to the exhaust pipe of his car. He placed the other end of the hose through one of the car’s windows, then sat in the front seat and turned the ignition key.

On Jenkins’ death certificate, the coroner wrote that the principal cause of death was “suicide by carbon monoxide gas” and the contributory cause was “mental depression and alcohol addiction.” I shook my head as I read it and whispered the two words I believed were missing: “Meuse-Argonne.”

As I commemorate Memorial Day in 2022, my search for the names of the Roman Catholic High School alumni who gave their lives in World War I enters its tenth year. With fifteen names yet to be found, it seems paradoxical to conclude I may have already found Roman’s final casualty of the Great War.

I’m certain that when the remaining names are revealed, two words will resonate among them: Meuse-Argonne.

Chris Gibbons is a Philadelphia-based writer and President of the Alumni Association of Roman Catholic High School. His recently published book, “Soldiers, Space, and Stories of Life,” is available on amazon.com.

My grandfather, Jasper K. Lewis served in Company E, 319th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Division in the Meuse-Argonne. He reported for duty at Camp Lee Virginia on April 1st 1918. ON May 17th the division embarked for France. They landed at St. Nazaire on May 31st. On August 1st the division went up on the line. His company participated throughout the Meuse-Argonne offensive. By the conclusion of hostilities on November 11th, Company E had suffered 118 wounded in action, 30 killed in action, and one succumbed to disease for a casualty rate of 47%. This was typical for infantry units in that battle.