Logan Chipkin: Remembering James Logan, Philadelphia’s first scientist

Near the intersection of Locust Street and 13th Street, you will find the Library Company of Philadelphia. The library holds about 500,000 books and thousands of other first edition items, such as the Mayflower Compact, original maps, and famous books. Although founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1731, the famous library would not be a landmark of Philadelphia without the efforts of Franklin’s own mentor, James Logan (1674-1751).

Logan was a prime reason that Philadelphia was a bastion of scientific progress in colonial America. He was an early American Renaissance man, having succeeded not only in science but also in business and politics. While Franklin is famous for his wide array of abilities and accomplishments, he must have seen in the elder Logan that such a variety could exist in one person in the first place.

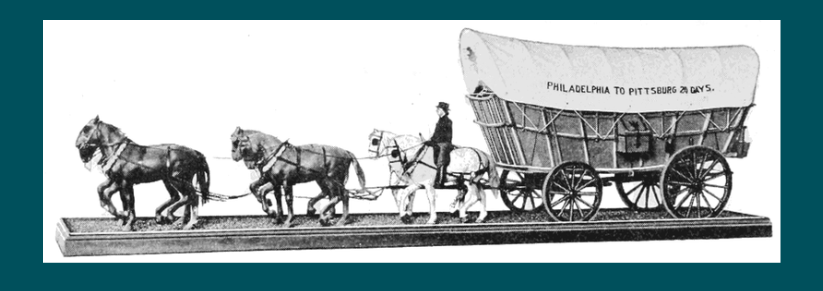

Logan’s intellectual appetite was insatiable. He was competent in an enormous number of languages, including Greek, Biblical Hebrew, French, and Italian. He devoured the classics and took copious notes in their margins. He taught himself the calculus of Isaac Newton, which was still very new in the late 1600s; he invented or introduced (the historical record is conflicting) the Conestoga wagon to the public, which was used to transport animal hides in the fur trade with Native Americans. He contributed to botany, calculus, optics, and astronomy.

Logan was a prime reason that Philadelphia was a bastion of scientific progress in colonial America.

The Irish-born James Logan began his life in Philadelphia in 1699, when William Penn asked the young man to serve as his secretary. Penn had been impressed by Logan’s abilities in the shipping trade and knew he had recruited a gem. A few years later, Logan became Presiding Judge at the Court of Quarter Sessions in Pennsylvania. He even served as acting governor of Pennsylvania when the incumbent died. By the 1730s, Logan had successfully built ironworks and fur trade businesses.

Finally established and financially comfortable, Logan pursued his scientific interests in full. In addition to his scientific discoveries, Logan served as something of a connective tissue in the burgeoning network of scientists across the Western World (the Scientific Revolution had only ended a few decades ago). He taught Latin to the famous American botanist, John Bartram, and introduced him to Swedish biologist Carolus Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy.

Logan eventually took Benjamin Franklin under his wing. The pair of virtuosos would often discuss science and philosophy at Logan’s estate in North Philadelphia, called “Stenton”. While Franklin’s experiments with electricity are part of our nation’s collective consciousness, it is far less known that the Founding Father had consulted Logan about his results before Franklin sent them to England.

In the 1730s, after a fall rendered Logan physically lame for the rest of his days, the Philadelphian wrote about philosophical manners from a secular perspective. His treatise, The Duties of Man Deduced from Nature, was only recently rediscovered. In one section, Logan expounds on mathematics, harmonics, and medicine. In another, he develops a nonreligious moral philosophy, the only such work written in colonial America.

Books were as much a passion to Logan as science was. In 1733, he translated the Roman Cicero’s Cato major in 1733, which Franklin then published with his own press in 1744 — yet another collaboration between the Founding Father and his mentor.

While Franklin’s experiments with electricity are part of our nation’s collective consciousness, it is far less known that the Founding Father had consulted Logan about his results before Franklin sent them to England.

Logan came to own over 2,600 books. Towards the end of his life, he chose to leave these volumes for his fellow Philadelphians. In 1754, the Loganian Library was built and entrusted to Logan’s two sons as well as his protégé, Benjamin Franklin. As Logan wrote to Franklin, his collection included “A good Collection of Mathematical Pieces, as Newton in all three Editions, Wallis, Huygens, Tacquet, Dechales…in all Sizes.” He possessed works of ancient mathematicians, writings in astronomy, and books about natural history. In 1792, long after Logan’s death, his book collection was transferred to the Library Company of Philadelphia, where they can still be found.

On October 31st, 1751, Logan died as “the region’s most influential statesman, its most distinguished scholar and its most respected…citizen.” Stenton is now a historic house museum at 4601 North 18th Street, in the appropriately-named Logan neighborhood of Philadelphia.

From 1699 to 1751, Logan held nearly every honor and responsibility of Philadelphia’s provincial government. He was also an original scientific and philosophical thinker, and he helped to make Philadelphia an Enlightenment hub in the growing worldwide network of scientists. Aside from his impact on Philadelphia’s political and scientific character, perhaps Logan’s greatest contribution to Philadelphia is his protégé, Benjamin Franklin. We may never know just how influential Logan was in Franklin’s development into a historical titan, but it remains plausible that the long-haired man with a smirk would not have taken the life path that he did without James Logan’s mentorship.

James Logan has received very little biographical work by historians. Irma Jane Cooper’s volume, The Life and Public Services of James Logan (1921) is a meager account, and Frederick B. Tolles’ James Logan and the Culture of Provincial America (1957) corrects for some of Cooper’s inaccuracies. Still, it is something of a mystery as to why Benjamin Franklin’s mentor is not a household name in Philadelphia. But his ideas and passion for books live on at 1314 Locust Street, in the halls of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Logan Chipkin is a freelance writer in Philadelphia and a contributor to Broad + Liberty. @ChipkinLogan