Beth Ann Rosica: Why phone-free schools are only the beginning

My wish for 2026 is to significantly decrease the amount of screen time in schools.

The Senate Education Committee recently passed legislation to ban cell phones in schools. The bill has bipartisan support and the sponsors are optimistic about it passing the full Senate and House. Elected officials on both sides of the aisle understand the harmful effects of non-stop cell phone use during the school day.

Yet cell phone-free schools are just the first step towards improving our education system and our kids’ overall mental health.

Since the extended school closures, classrooms across the Commonwealth have changed significantly — and not necessarily for the better.

In most school districts, every student is assigned a personal device to use over the course of the school year. Even in elementary schools, most students are given an iPad or tablet to complete assignments both in the classroom and at home.

Prior to 2020, the majority of elementary schools had a limited number of devices that were used for specific purposes or assignments. Students completed work on paper and turned it into the teacher directly. Even at the middle and high school levels, students completed tasks and homework on paper.

Fast forward five years and every middle and high school student has some type of device where they complete the bulk of their work. During lockdowns, school districts were forced to issue devices to every student in order to participate in remote learning. Yet, when the schools reopened after the extended closures, the devices were here to stay.

As an older parent — I’m 58 with a 16- and 18-year old — I realize that my perspective may seem antiquated. Some label me a luddite. Perhaps I am.

But I firmly believe that our education system was much better prior to the invasion of technology into the classroom.

That’s not to say that there aren’t appropriate uses for classroom technology, but rather, the devices have replaced meaningful instruction, resulting in an inferior education system.

After the school closures, many teachers continued to provide instruction as if the students were still participating remotely. One of my children who was in high school at the time remarked that school never really went back to normal. Teachers used the devices to provide content material and assignments were submitted electronically. Even math problems that were solved on paper were ultimately uploaded to a learning management system.

Group and project work decreased significantly, as did reading full length novels. With reduced attention spans, many teachers adapted and cut back on more rigorous assignments.

And what do we have to show for that?

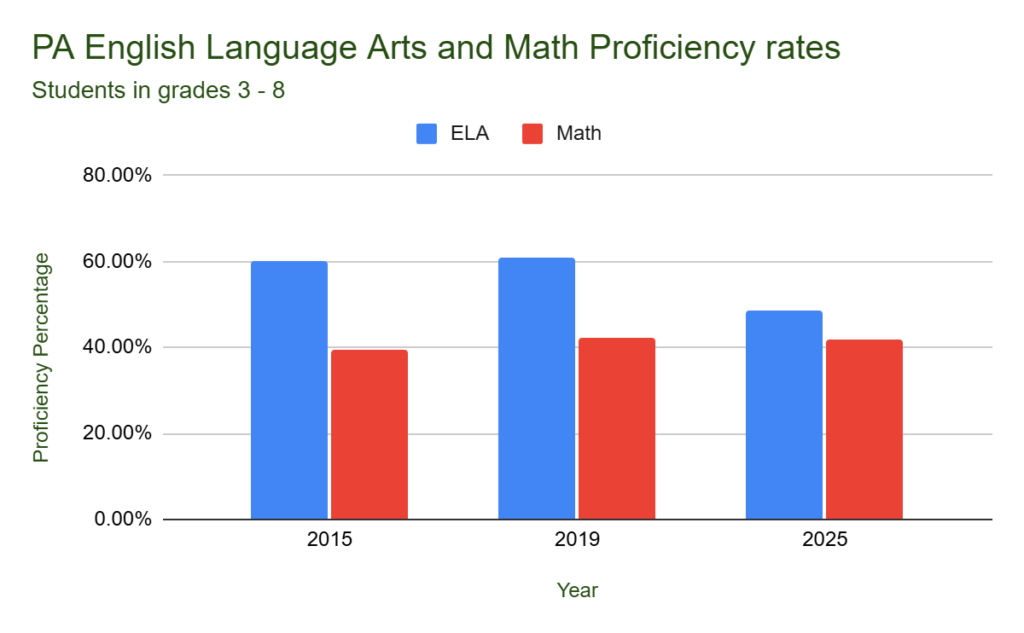

According to state standardized testing, the PSSA scores show that on average across the state students in elementary and middle school are less proficient now than they were in 2019. Over the last ten years, student proficiency in math has remained mostly flat while reading and writing proficiency decreased significantly.

While standardized testing is not necessarily the best measure of student performance, it is the only system we currently have to assess academic outcomes. The latest testing shows that only 48.5 percent of students are proficient in reading and writing and only 41.7 percent are proficient in math.

These numbers are staggering. Less than half of our students in grades three through eight are able to read, write, or do basic math at grade level.

Clearly, technology is not solving the problem.

Our kids spend an excessive amount of time online both in and out of school, despite recommendations to the contrary.

In 2019, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) issued screen time guidance. A CHOP pediatrician said, “screens should not replace parental and human interaction with a child.” She further cautioned “excessive screen time is associated with a number of health issues, including depression and obesity, and can also have a negative impact on a child’s sleep.”

Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a policy statement in 2016, updated in 2022, warning parents about the negative impacts of prolonged media use.

“Research evidence shows that children and teenagers need adequate sleep, physical activity, and time away from media.”

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry states that children ages eight to eighteen spend an average of seven and half hours on screens daily.

If experts are concerned about excessive technology use, why are we using devices as the primary instructional tool in most classrooms?

An overreliance on technology may also be related to reduced reading and writing proficiency.

Research shows that the ability to manually write letters and words is causally related to reading and comprehension. A study demonstrates that the process of printing letters impacts an area of the brain that is related to reading competence.

“Imaging results showed that children who had printed the letters had greater activation in the left fusiform gyrus (an area of the brain) during letter perception than children who had learned the letters without printing practice.”

A later study confirmed the results that brain activity is different for those children who learn to write letters manually versus those who learn to write by tracing or using a keyboard.

There is “evidence of direct neural links between handwriting quality, a skill that has been strongly associated with higher level writing skills and reading, and neural processing underlying phonological processing, which is thought to be causally related to reading acquisition.”

Perhaps one reason for declining reading and writing proficiency is related to the method of instruction — typing letters on a device is very different from tracing or writing them manually.

Our schools need to get back to basics and focus on live instruction from a professional who has the knowledge and experience to help students acquire foundational skills. Our students are not monolithic beings — they do not respond in the same way or at the same pace.

Teaching is an art and a science which technological devices cannot replace. Technology can supplement and enhance, but it can never replace actual teachers and competent instruction.

I often hear a counterargument that students must be prepared to work in the real world where technology is used in every profession, and I don’t disagree with that point. But there is a vast difference between supporting the instructional process with technology and replacing actual instruction with devices.

My hope for 2026 is a return to a simpler, more effective instructional model where students learn and achieve without an overreliance on technology — at the very least, we need a more balanced approach.

Beth Ann Rosica resides in West Chester, has a Ph.D. in Education, and has dedicated her career to advocating on behalf of at-risk children and families. She covers education issues for Broad + Liberty. Contact her at barosica@broadandliberty.com.

In his eulogy for his favorite college professor, President Garfield described the best possible college education as that professor sitting on one end of a log, and the student on the other.