Ben Mannes: Philadelphia’s “Driving Equity” law — one year later

Last week, Philadelphia lawmakers celebrated the first anniversary of the Driving Equality law, a Philadelphia municipal ordinance restricting Philadelphia police from making traffic stops for eight Pennsylvania vehicle code infractions. The proponents’ stated goal was to reduce anecdotal instances of traffic stops based on racial profiling and the perception of racial imbalances in municipal law enforcement.

Their mission was accomplished. However, statistics culled through municipal and nonprofit data centers circulated throughout social media, gleaning a potentially grim side effect of the city’s celebrated policy.

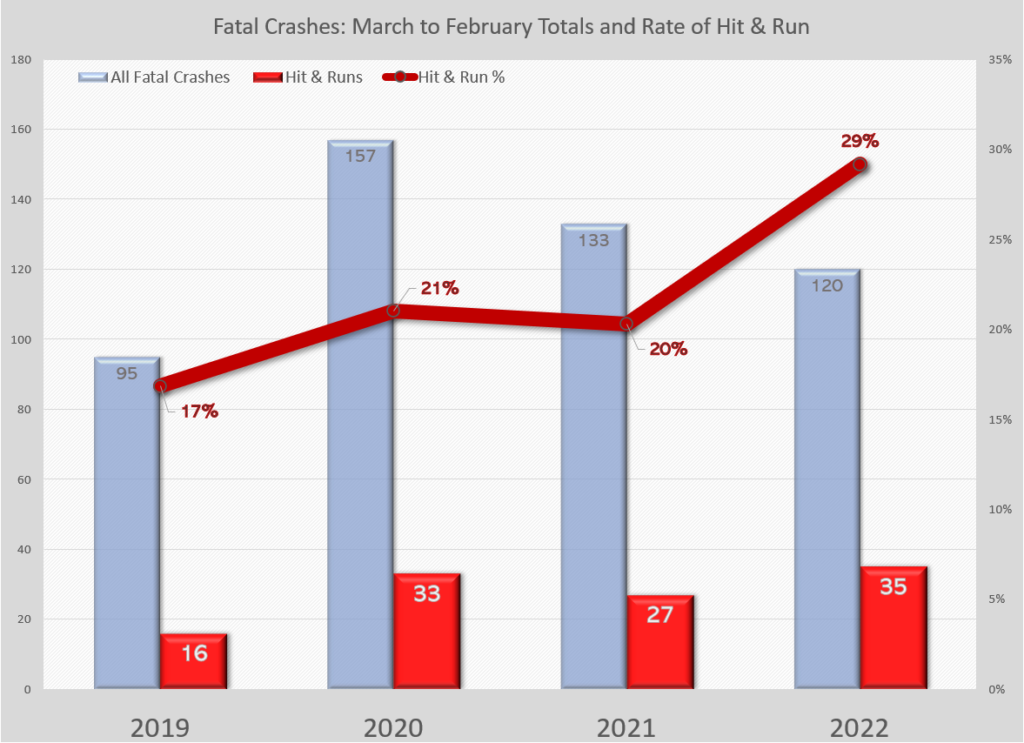

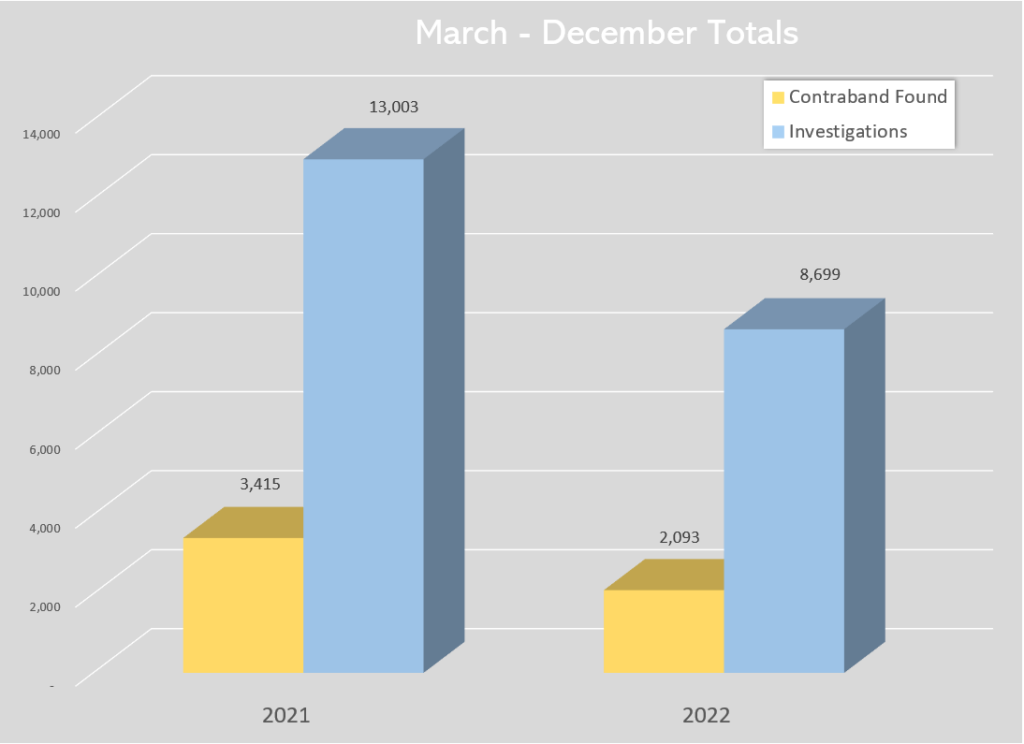

According to public data, the rate of fatal hit and run crashes in the city of Philadelphia increased by 45 percent, from 20 percent to 29 percent since the Driving Equality law passed, making up for at least 914 hit and run crashes this year — more than double the 2019 total. At the same time, as Philadelphia police are no longer availed of the reasonable suspicion gleaned from eight types of traffic stops that they once had, the number of vehicle searches gleaning arrests decreased by 33 percent, and a 39 percent decrease in contraband (including narcotics and illegal guns) was seized.

Even with the statistical rises of traffic-related fatalities and decreased number of guns and drugs seized, the law’s own proponents say their own stated goals associated with the law have not been fully achieved. According to Councilmember Isaiah Thomas, the law’s sponsor, the Philadelphia Police Department is still not publishing data that showing the amounts and types of traffic stops made by officers, a year after the changes went into effect. This is largely because the vast majority of traffic stops conducted by law enforcement do not escalate to a vehicle search or arrest – most end with warnings or traffic tickets.

In an email response to Broad + Liberty, Philadelphia Police spokesman Miguel Torres wrote “The Philadelphia Police Department began operating under the conditions of the Execution Order on 03/03/22, which modifies Motor Vehicle Code Violation enforcement for 8 secondary violations. The Driving Equality Bill does NOT LEGALIZE 8 certain PA Motor Vehicle Code infractions. Rather, the law modifies the way they can be enforced by the department, by making them enforceable as secondary violations.”

He continued: “Unfortunately, we currently do not have the technical capacity to report out on the effects of the Driving Equity provisions, as our current system does not have the capability to capture primary and secondary stop violation information at a granular level. The PPD continues to work with other city agencies to set the necessary systems in place that will allow us to more accurately capture the data.”

In a statement published by Metro, Thomas confirmed that the PPD and Kenney administration “hasn’t been able to come into compliance” with companion legislation that requires the city to more closely track details of vehicle stops. A data dashboard was supposed to be set up no later than October 2022, according to the law.

Regardless, ranking sources within the PPD confirm the correlation between the decline in stops and increase in traffic-related crimes. After the “driving equality” legislation passed City Council in 2021, Commissioner Danielle Outlaw issued an Execution Order in March 2022, prohibiting officers from making primary stops for eight vehicle code violations, which primarily include observed vehicle deficiencies that would render the vehicle unable to pass state safety inspections.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Thomas touted that traffic stops associated with vehicle code violations dropped by 54 percent, or nearly 16,000 interactions, between 2021 and 2022, despite his claim that such data is not being accurately tracked by the PPD, based on his work with the Defender Association of Philadelphia to study traffic stops that took place in the first seven months of the legislation’s implementation.

Thomas rejected criticism that the legislation has made the city less safe or hampered efforts to confront the gun violence crisis. “Shame on anybody who tries to say that because we’re fighting for the plight of black people that we’re trying to put ourselves in a position to make the city more dangerous,” he said. “At some point, somebody has to stand up and say ‘black people know what’s best for black people.”

When presented with the increase in hit-and-run fatalities since Thomas’s signature bill was passed, Max Weisman, Thomas’s Communications Director, challenged the correlation “Can you help me understand the correlation? Driving Equality reclassifies 8 minor traffic violations such as something hanging from the mirror and a single broken taillight. While I know social media advocates would have us believe that this reclassification leads to less safe driving, our office does not share this analysis. Driving Equality reclassifies minor vehicle violations such as something hanging from the mirror. That violation is still a violation that an officer can still enforce, just not with a traffic stop. For serious violations such as driving through a red light is still a violation that can be enforced through a traffic stop. In fact, as the data suggests, officers pulled over more vehicles for these types of traffic stops (running a red light or running a stop sign) than they did prior to Driving Equality.”

Weisman’s choice of the “obstructed view” violation (having something hanging from the mirror) did not include other stops that the PPD is now prohibited from making, which include expired registration(s), missing or misplaced license plates; a broken head or brake light, bumpers that are missing or improperly affixed, and expired inspection or emissions sticker. The last two are of critical importance to vehicle safety, as Pennsylvania has one of the costliest inspection processes in the nation, certifying the braking and safety capabilities of each vehicle registered in the Commonwealth.

Weisman did add a caveat: “That being said, Councilmember Thomas has always been open about amending Driving Equality if presented with analysis that suggests that certain violations should be removed or added to Driving Equality” leaving room for possible amendments should a deadly correlation be proven by the new municipal administration coming within the following year.

Philadelphia was the first major U.S. city to ban the so-called pretextual stops for some infractions, a tactic that some law enforcement agencies have encouraged as a means of searching cars for illegal guns or drugs. Since its passage, the Pennsylvania Law Enforcement Accreditation Committee (PLEAC) has sought to revoke the PPD’s state accreditation based on the law’s implementation and the PPD union, Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 5 has a pending lawsuit against the city in an effort to overturn the execution order.

Abington Police Chief Patrick Molloy, a Philadelphia native and one of the PLEAC members who voted to revoke PPD’s accreditation told Broad + Liberty “At a time when aggressive driving, crashes with injuries, etc. are on the rise, our profession needs all available tools to reduce accidents and injuries. Part of our approach in Abington and on a state level with PLEAC is education, traffic calming studies, and enforcement of the entire vehicle code.

In addressing Thomas’s concerns, Molloy continued “I understood issues related to profiling, pretext stops, disparate impact, etc. and as leaders, we need to do everything we can to hold our officers accountable, making sure we are treating everyone with respect, holding our officers to the highest of professional standards to build trust and partner with leaders in our minority communities to do so. However, most people don’t know how much oversight exists in professional police agencies, to include body cameras, citizen complaint processes, adherence to professional accreditation standards, etc. To create policy telling officers that they don’t have the ability to enforce the vehicle code fair and impartially is a terrible message. We need to enforce the vehicle code without consideration of race, as our oath requires.

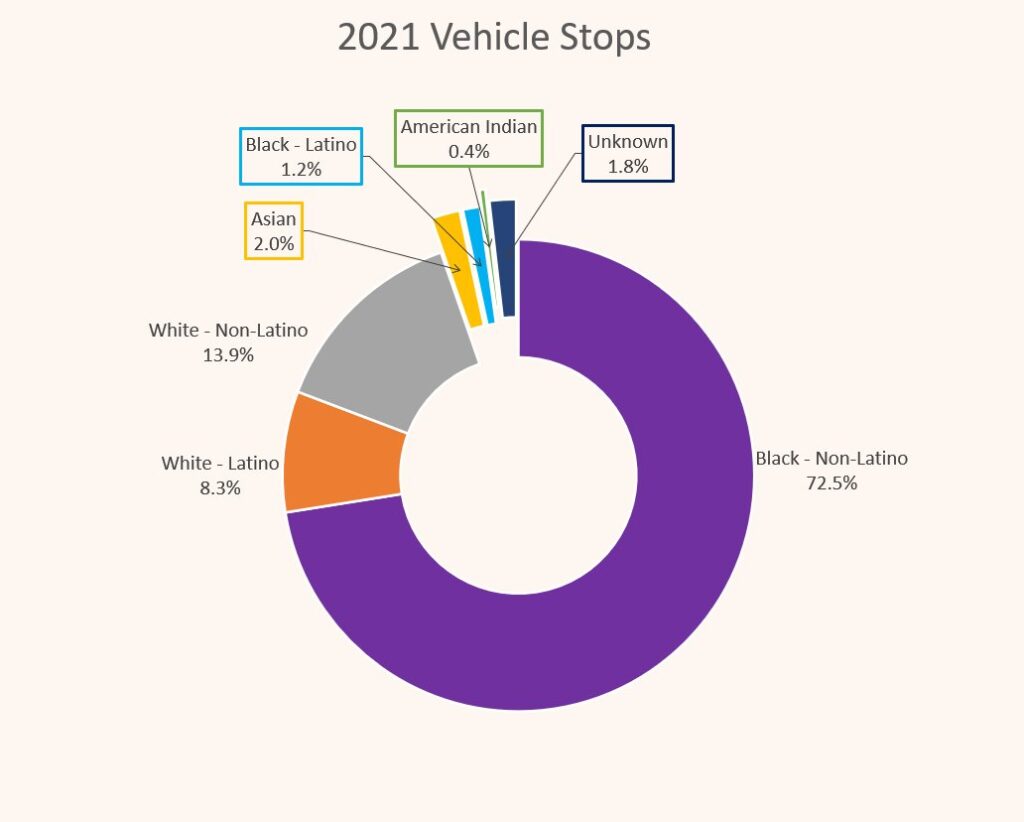

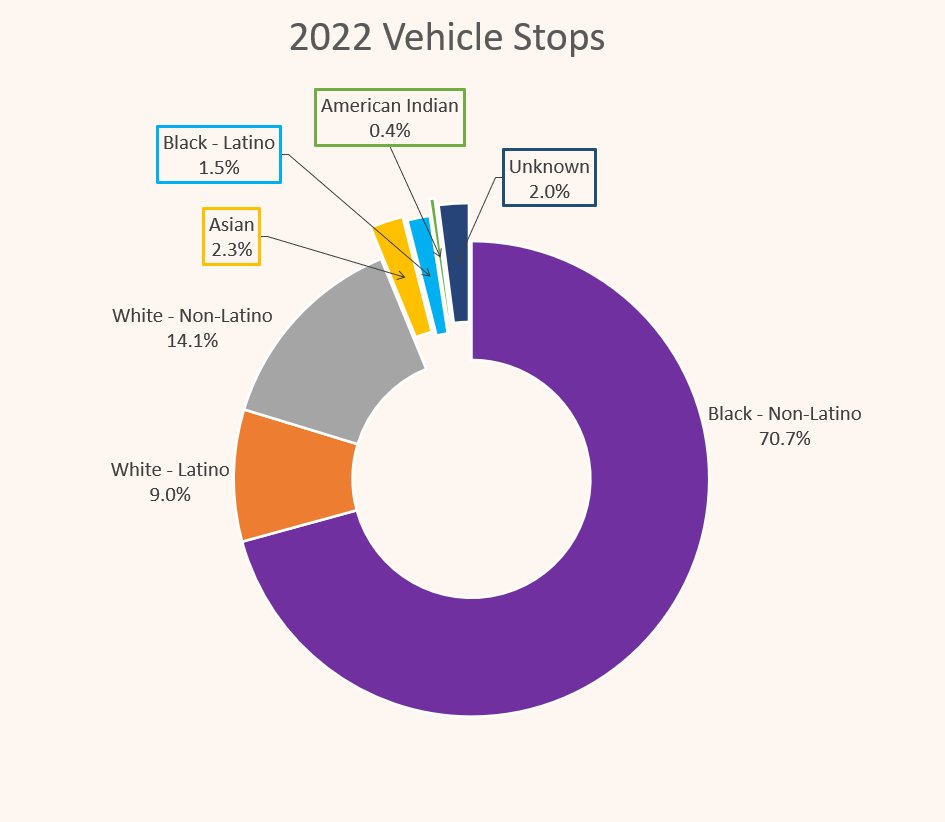

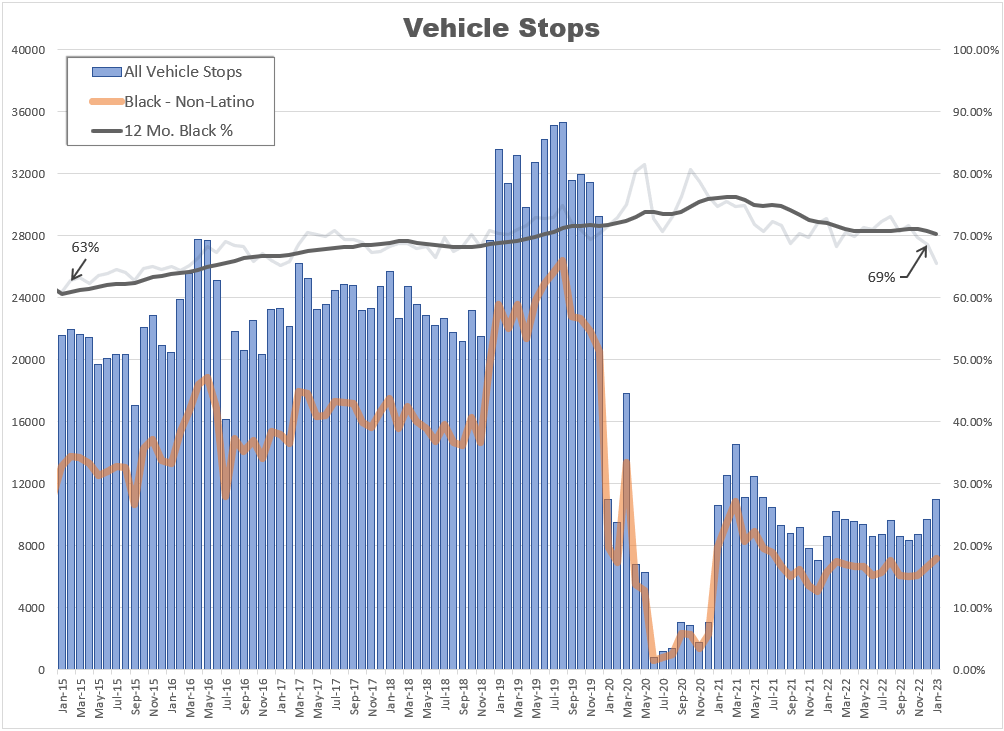

Thomas has said car stops are an ineffective means of seizing illegal guns, and that they exacerbate what’s become known as “driving while black”. In pressing for the legislation, Thomas’s office cited 2019 data showing that 72 percent of vehicle code violations were assessed against black drivers while black people make up 43 percent of the city’s population, while leaving out context showing that the Patrol Service Area concept implemented by then-Commissioner Charles Ramsey deployed more law enforcement resources to communities with the most reports of crime, creating the unaddressed “chicken and egg.”

This may account for why the percentage of African Americans stopped has remained virtually unchanged since the Driving Equality law was passed. This is shown in the open-source data chart below obtained by Broad + Liberty, outlining the racial makeup of vehicle stops in 2021 and 2022 – illustrating the data that the PPD said they can’t obtain.

Another statistic shows that traffic stops were declining amid many proactive policing tactics before Thomas’s law took effect, correlating with politicized prosecutions of police officers by DA Larry Krasner. According to police data, there were an average of 330,000 vehicle stops each year between 2015 and 2019. The number was more than halved in 2020 and 2021 following the George Floyd riots.

In contrast, the State Police and surrounding jurisdictions around Philadelphia are still enforcing the vehicle code in compliance with state law, as noted by Chief Molloy “In Abington, simple car stops often result in arrests for outstanding warrants, recovery of firearms, and removing violent offenders from our streets. Why, at a time when violent crime and aggressive driving is on the rise, would you take a valuable tool away from our officers? This sends the wrong message, and all of us can agree that we need to always be vigilant while simultaneously ensuring that our officers are living up to our oath, following the rules of criminal procedure, and never violating the constitutional rights of our fellow citizens.”

While the Driving Equality ordinance may address Thomas’s goal of reducing the “humiliation” of a traffic stop, it also raises questions regarding the safety of the citizens, especially in poorer communities, where vehicles with safety deficiencies may be on the road.

A. Benjamin Mannes, MA, CPP, CESP, is a Subject Matter Expert in Security & Criminal Justice Reform based on his own experiences on both sides of the criminal justice system. He has served as a federal and municipal law enforcement officer and was the former Director, Office of Investigations with the American Board of Internal Medicine. @PublicSafetySME

Such a stupid policy. Working brake lights and turn signals are a safety policy. We enforce these laws because disobeying them can put others’ lives at risk.