Thom Nickels: Clare Boothe Luce — a look back at a fascinating American life

When I inherited my great aunt’s desk (purchased by her father from Freeman’s Auction House in 1934), I knew its contents fairly well. I knew that among the scrapbooks and photographs, there was a long typewritten letter signed by Clare Boothe Luce, playwright, member of Congress, editor at Vogue and Ambassador to Italy (appointed by President Eisenhower) in 1953.

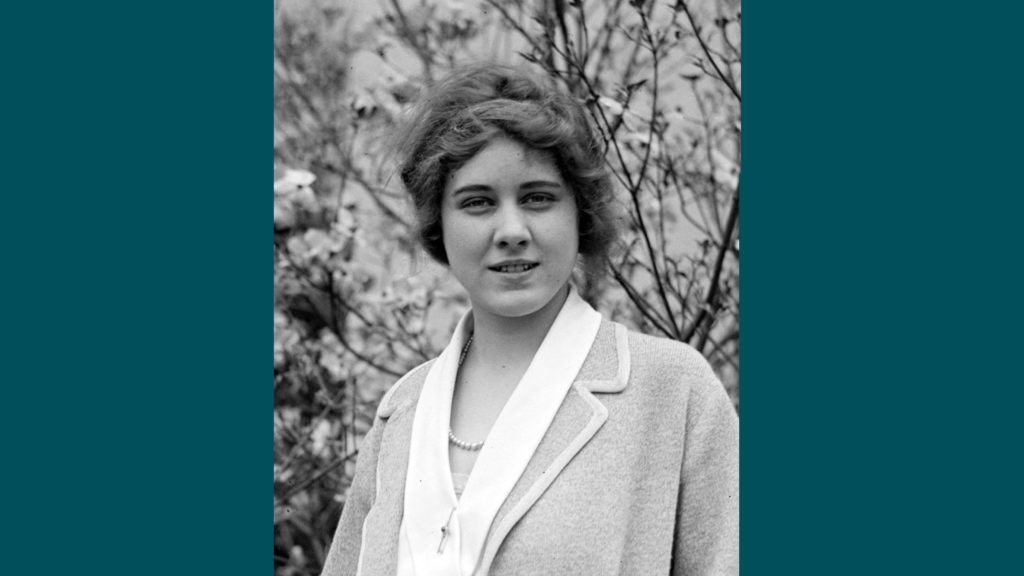

TIME magazine had also called Clare Boothe Luce “the Pre-eminent Renaissance woman of the Century.”

Luce, a Republican feminist, was a hero of my great aunt’s. I dismissed my great aunt’s adulation then because Luce was a Republican (I was a radical Democrat), but the letter forced me to take another look at Luce’s life, a world filled with psychedelics, elevator rides, stuttering and the glamor of fame.

READ MORE — Thom Nickels: The last days of Walter Gropius

Luce’s father was a descendant of John Wilkes Booth. To separate the family from Lincoln’s assassin, biographers claim that either Luce’s grandfather or Luce herself added an ‘e’ to the family name.

Luce dropped out of school at age sixteen and married a Manhattan millionaire at twenty with whom she had one daughter. Her husband’s ribald alcoholism caused her to seek a divorce in 1949, two years into the marriage. The death of her daughter Ann in an automobile accident led her to look into psychoanalysis and religion in 1945. Psychoanalysis did not work for her, but a chance meeting with Bishop Fulton Sheen initiated a series of meetings which resulted in Luce’s conversion to Catholicism.

Luce wrote in McCall’s magazine that she had to become Catholic “in order to rid [her] burden of sin.” A Vanity Fair article reported that Luce was convinced she would meet her daughter Ann in the afterlife.

That conversion did not come easy. Thomas Reeves, in his 2002 biography of Bishop Sheen, “The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen,” writes that Luce was a “tough convert” who “lashed out at Sheen” frequently. Sheen himself was quite amazed at the level of profundity and analysis from Luce during the conversion process.

But when Luce, a personal friend of John F. Kennedy’s, told the president about her conversion, JFK told her, “Why strap the cross on your back? I never thought a Catholic religion made sense for anyone with a brain.”

Still, as a divorced woman, when she met Henry Luce, the publisher of TIME magazine, she knew that if she married him as a Catholic, she could not sleep with him because that would be considered a mortal sin. Her solution to the problem was to live with Henry as “brother and sister.” As Vanity Fair reported, “With the sexual pressure lifted, the Luce marriage went into high gear.”

Perhaps the celibacy arrangement of their marriage wasn’t all that difficult considering the fact that Henry was said to have sexual problems and could not consummate the marriage.

According to Luce’s biographer, Sylvia Jukes Morris, another result of Luce’s conversion to Catholicism was that it put a damper on her natural talent for writing “nasty plays about women.”

In fact, Luce, who wrote her famous play The Women in three days, gave up playwriting after her conversion. A Miami Herald reviewer, commenting on the second volume of Luce’s biography, wrote: “Conversion ruined her creativity. Henceforth, she became preachy; her prose, which had been praised for its acerbic honesty, grew hesitant and predictable. The threat of damnation did not stop her from attempting suicide on multiple occasions over her husband’s infidelity.”

Clare Boothe Luce also never wanted to stop living the life of a young woman.

At age 80, she told Morris she was “having an attack of the dismals.” Morris asked her what she meant. Luce responded, “It’s Saturday night and I don’t have any beaus. A homosexual Admiral would be good. He’d come in a uniform but at the end of the evening I wouldn’t have to put out.”

When President Eisenhower appointed Luce Ambassador to Italy, the Italian people felt insulted because Luce was not a man. Luce was also treated in less than ambassadorial terms by her fellow diplomats in the United States. Yet after only one week in Italy, Ambassador Luce won over the Italian people.

In Miami in 1965–66, Luce met another celebrity in an elevator.

This time it was Abbie Hoffman, who had the chutzpah to ask Luce if she had ever taken LSD. Luce said she had, to which Hoffman replied, “I took it once.” Luce, a frequent LSD user, exclaimed, “Only once?” Morris writes that Luce’s departing words to Hoffman were, “See you in Nirvana.”

The letter from Luce to my great aunt is dated 1956 and was written in response to a letter about a long-forgotten minor political issue. While hardly a collector of autographs, I did check the signed letter’s worth and found it to be somewhere near $165.00. (This comes nowhere near the value of the signed personal letter to me from Elizabeth Taylor, valued at $1,200, another story for another time).

Luce’s letter to my great aunt caused me to look even deeper into Luce’s life.

I discovered that Henry Luce (1898–1967) had a serious stutter as a child. Luce’s stutter was apparently caused by a tonsillectomy at age seven when the anesthesia wore off before the operation was over. The stutter caused him to be made fun of and mocked as a student. When he transferred to an English boarding school, a “speech correctionist” taught him to take a short breath before each sentence. This alleviated much of the problem, but his stutter never entirely disappeared.

The stuttering connection interested me because I, too, stuttered as a child. I’d go red in the face, say “um” a million times, barely able to get a few words out before gasping for breath. In high school, I’d plead with certain teachers to allow me to do two or three written classroom reports rather than one oral one. I was still stuttering as a freshman in college. The stutter left years later when I took a Learning Annex course on public speaking in Center City. The teacher, a former NYC ballet dancer, discovered how to fix it. She taught me how to breathe, à la Henry Luce.

It was, as they say, a miracle.

[Luce] did not believe in any censorship of thought, but she had major concerns about non-student agitators on American campuses whose only goal was to ignite riots and unrest.

At one point, Luce was talked into taking LSD by Clare, whom Morris says always wanted to try the latest thing. In 1959, LSD was the latest thing; it was also unregulated and there was no Dr. Timothy Leary on the scene. It was not only prescribed by psychiatrists for depressives and criminals but for the intelligentsia, who flocked to it as a way to enhance the mind. It was still all the rage at Harvard University when I lived in Cambridge in 1970. Professor friends of mine were always encouraging LSD as a “consciousness expander,” and it was not uncommon to see small tablets of “acid” being passed around after a dinner party.

Clare took her LSD under the direction of English philosopher Gerald Head. “She always had good trips,” Morris said in one interview.

No jumping out of windows thinking she could fly for Clare!

In 1997, the Washington Post reported that Clare’s LSD fascination occurred during her post-Catholic phase:

“She had been a fervent convert to Catholicism in 1946, but as her religious enthusiasm waned, she was perhaps looking for a new mystical experience. LSD provided this to some extent because she usually had enjoyable and illuminating trips.”

Substituting religion with LSD was certainly popular during the countercultural years of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The drug was labeled a gateway to solving life’s metaphysical mysteries, but all too often it became a sensual color experience, a hallucinatory smorgasbord where one “saw” eyes in a mushroom or small fairies dancing amid the designs on elaborate wallpaper. Bad trips were terrifying, akin to descending into a dark netherworld. In some cases, the user came to believe that he or she could do fantastical things, like jump out of a window and fly like Peter Pan.

This happened to an artist acquaintance of mine in Boston, who jumped out of his high rise apartment window thinking he would take to the air like an angel with wings.

Clare Boothe Luce appeared on William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line” more than any other guest in the history of that show. Buckley was also a good friend, whereas Dorothy Parker was a vehement detractor. Buckley was the eulogist at her memorial service at St. Patrick’s cathedral in New York, where the two of them sat side-by-side some years before at the memorial service for Grace Kelly. It was at that service that Luce whispered to Buckley, “This is how I would like to go out.”

Clare Boothe Luce was a strong advocate for free speech. Despite her conservative politics, she encouraged the exchange of ideas in left-right debates in universities across the country. She did not believe in any censorship of thought, but she had major concerns about non-student agitators on American campuses whose only goal was to ignite riots and unrest.

In an article entitled “Handling Campus Activists,” she wrote: “The soft approach of appeasement adopted by university administrators only provoked more demonstrations and an increase in size and violence.”

For a woman surrounded by luxury most of her life — a stellar home filled with servants on Diamond Head on the island of Oahu, Hawaii — her funeral was remarkably, shockingly simple.

Her coffin was a simple pine box, and her service was an austere Trappist Mass at Mepkin Abbey in South Carolina with just a few people in attendance.

Thom Nickels is a Philadelphia-based journalist/columnist and the 2005 recipient of the AIA Lewis Mumford Award for Architectural Journalism. He writes for City Journal, New York, Frontpage Magazine and the Philadelphia Irish Edition. He is the author of fifteen books, including ”Literary Philadelphia” and ”From Mother Divine to the Corner Swami: Religious Cults in Philadelphia.” “Death at Dawn: The Murder of Kimberly Ernest” will be published later this year.