Kyle Sammin: Pa. State House map slants toward Dems and away from the state constitution

Pennsylvania’s Legislative Reapportionment Commission (LRC) has released its proposed state house and senate maps. Questions abound about the decisions that led to them, with state Republicans expressing special concern over the state house map.

Every redistricting process produces aggrieved incumbents, but this one appears almost exclusively to have discomforted those on one side of the aisle. Where twelve Republican incumbents find themselves in the same district with another Republican incumbent, the same is true only for two Democrats. And that number for Republicans may rise to fourteen, depending on the results of a special election pending in the 116th district, in Luzerne County.

Compared to previous decades’ redistricting efforts, the number of incumbents forced into primaries is unusually high. That alone is enough to guarantee objections, given that Pennsylvania’s constitution requires members of the General Assembly to live in their districts (not true for federal Congressional districts, for example).

But the process of drawing the proposed state house maps should cause anyone paying attention to doubt the neutral principles supposedly at work by the technocratic committee. The district lines are not especially weird-looking. At least not compared to those of the past, so the LRC map may pass the eyeball test. But in another important way, the committee clearly failed. The proposed lines split 63 municipalities a total of 102 times — far more than what is necessary to achieve equal population across districts.

READ MORE — Eisenberg + Sammin: Redistricting in Pennsylvania — What Pennsylvania’s Colonial past tells us

The line-drawers appear to have aimed at the goal of making the total percentage of Democratic-leaning districts equal to the percentage of the statewide Democratic vote. That is the current trend in left-leaning redistricting, a change even from three or four years ago when goals of compactness and keeping communities together were the watchwords of reformers. The new fad of proportionality comes at the expense of the older, more recognizable goals and works against the principles set forth in the 2018 Pennsylvania Supreme Court case of League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Commonwealth.

Consider Berks County’s new districts as an example. The average statewide district size is 64,098 people. With a population of 428,849, Berks County is large enough to contain about six and two-thirds districts. The proposed map accomplishes this by placing six districts (the 5th, 126th, 127th, 128th, 129th, and 130th) completely within Berks. Portions of two other districts (the 99th and 124th) take in the remaining voters.

So far, so good. But the LRC seemingly had another goal in mind for Berks County: making a third state house seat Democratic. This is possible, but only by discarding every other principle once considered to be a guideline of honest, non-partisan districting.

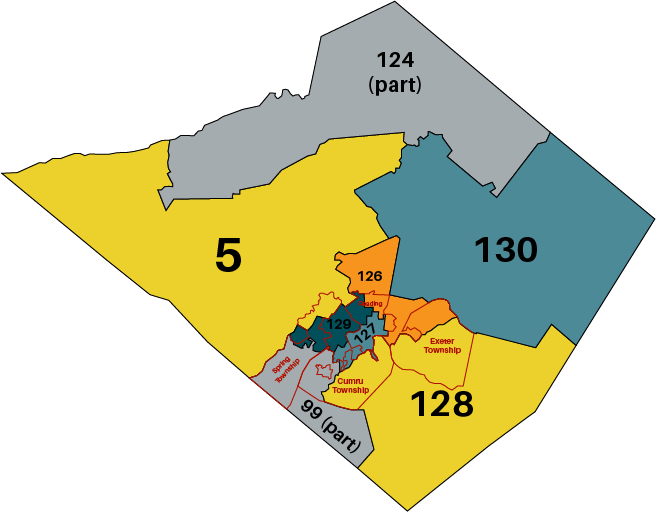

The Clever map of the Pa. Legislative Reapportionment Commission

Look at the map below, which contains the LRC’s proposal for Berks County. At first glance, it is not so bad. The shape of the districts is not that different from the current lines, and if anything is a little smoother.

But there is more to this proposed map than meets the eye. It goes well beyond what must be done, making a virtue of that necessity to justify cracking natural community boundaries. As the text of the proposal notes, three of Berks County’s municipalities are each divided among three districts by the plan (Reading, Cumru Township, and Spring Township.) Another, Exeter Township, is divided twice. Population equality will often require such divisions. Larger municipalities, like Reading, are too big to be contained in a single district.

The map below, with the municipal lines superimposed over the proposed House districts, shows just how shattered the four communities become on the LRC’s map. Article 2, section 16 of the state constitution says that “[u]nless absolutely necessary no county, city, incorporated town, borough, township or ward shall be divided in forming either a senatorial or representative district.” The LRC thoroughly ignored this binding rule in pursuit of its own agenda.

Does it look messy? That’s because it is. The web of boundaries crossing over each other shows the extent to which the LRC would break up natural communities in Berks County. For example, Exeter Township is divided between the 126th and 128th districts; Spring Township is split among the 5th, 99th, and 129th; and Reading is divided among three districts when it could easily fit within two.

The new fad of proportionality comes at the expense of the older, more recognizable goals and works against the principles set forth in the 2018 Pennsylvania Supreme Court case of League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Commonwealth.

The LRC plan also slights Reading’s Hispanic population in a way that goes against the prevailing trend of maximizing districts in which ethnic minority groups have a greater chance of electing a representative from their own community. The current 127th district has a Hispanic majority, as does the LRC’s new version of it. But the 126th could easily have also been majority-Hispanic, had the LRC wished it. Instead, the committee sliced off a section of Reading and appended it to the neighboring 129th district, which without that portion of Reading would lean Republican. This could mean decreased Hispanic representation in the General Assembly — something that might attract the attention of the federal Department of Justice.

Uneven districts favor state Democrats

Finally, the population deviations in the LRC’s map, while within the legal requirements, are clearly slanted to favor one side. The state constitution requires that districts shall be “as nearly equal in population as practicable.” Courts have interpreted this to mean a maximum ten percent deviation between the most populous and least populous districts — quite a bit more leeway than we see in federal districts. (That is to say, a district can be 5% more or 5% less than the average — currently 64,098.)

The LRC used that leeway in Berks County to maximize the three Democratic districts they drew. Each of the Democratic-leaning districts is close to as small as legally possible — the 126th, 127th, and 129th are undersized by -3.60%, -4.31%, and -4.62%, respectively. The three Republican-leaning districts entirely in the county — the 5th, 128th, and 130th — are oversized by 1.53%, 3.44%, 1.76%.

Legal? Yes. But hardly an act of disinterested neutrality. These less populous districts allow a significantly smaller number of mostly Democrats to exercise equal power in the legislature as a larger group of mostly Republicans. There will always be population variations, especially when the LRC is compelled not to divide communities. But the state constitution’s requirement that such districts be “as nearly equal in population as practicable” requires a good faith effort to reduce those deviations where they can.

What has been said here of Berks can be said about a dozen other counties across the commonwealth, including Lehigh, Northampton, and Centre Counties most prominently.

Of course, it’s easy to point out the flaws — redistricting is complicated. Is it equally easy to make a new map that avoids all of these problems?

Yes, actually, it is.

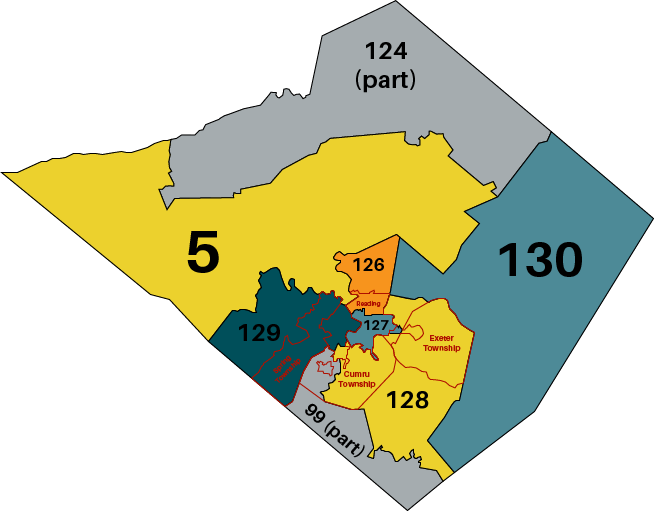

The map below shows what Berks County might look like if the LRC revised its plan to remedy all of the problems cataloged here.

Here, the splitting of municipalities is greatly reduced. Spring Township is in one district, not three. Exeter Township is also in just one, not two. Reading, with 95,112 residents, is too big to be all in one district, but here we have divided it only between two, not three. Cumru Township remains divided, but only in two districts, not three as before.

This revised map would also create two majority-minority districts where the LRC draft has just one. They are also slightly more compact overall. The biggest population deviation would be just -2.37%, making the districts more perfectly equal in number of residents.

All of these traditional aims of redistricting — the ones mandated by Pennsylvania’s constitution and the federal Voting Rights Act — can be satisfied pretty easily, as long as you don’t mind that a Republican could win an extra seat.

Kyle Sammin is a senior contributor to The Federalist, co-host of the Conservative Minds podcast, and resident of Montgomery County. He writes regularly for Broad + Liberty. @KyleSammin

So, the Republicans have to work harder for the Latino vote. The recent election showed that progress could be made at national levels. Time for the PA State Republican party to actually go to work to capture voting blocs it had written off previously and that the Democrat party typically takes for granted.

The GOP would rather rig the maps in favor of “Republicans and non-hispanic whites” like they’re doing in other states. Don’t believe that’s what they’re doing? Just read the late GOP strategist Thomas Hofeller’s emails.

So… wait the GOP opposes gerrymandering all of a sudden? Go tell that to the Texas, Georgia, Michigan, Ohio, North Carolina, and Wisconsin state legislatures, the CONSERVATIVE SCOTUS judges who gutted the VRA and the REPUBLICAN redistricting strategists who were caught red handed trying to rig districts in order to benefit “Republicans and non-hispanic whites” (their own actual words).

Do Republicans really expect anyone to listen to them when they start complaining about gerrymandering? Give me a break.