Sean Parnell: National Popular Vote would be bad for Pennsylvania … and the nation

For more than 240 years, the Electoral College has served as a vital institution that balances the important democratic principles on which the presidential election process is based, including federalism, checks on majoritarian power, and one person, one vote.

The Constitution established a system in which the states are sovereign political entities, not mere administrative subunits of the national government. The Electoral College embraces this federalist principle and ensures that every state, and the voters of every state, have a voice in choosing the president. It protects minority rights by ensuring that a candidate cannot simply run up the score in a handful of populous areas while ignoring the rest of the country, and it respects one person, one vote, which means that every voter is equal to every other voter within the state.

READ MORE — Enough of the lies about National Popular Vote!

The National Popular Vote interstate compact would toss aside this carefully crafted institution and replace it with a cobbled-together scheme that would eliminate Pennsylvania’s voice in the presidential election, giving voters in New York, Texas, and elsewhere control of this state’s 19 electoral votes.

Rather than doing the hard work of actually amending the Constitution to alter the Electoral College, the compact is an agreement between states whose members pledge to ignore the will of the voters in their own state and instead award their presidential electors to the candidate deemed to have received the most popular votes in all 50 states (plus Washington, D.C.). It goes into effect if states with a combined 270 or more electoral votes have joined, even if that’s only a minority of states.

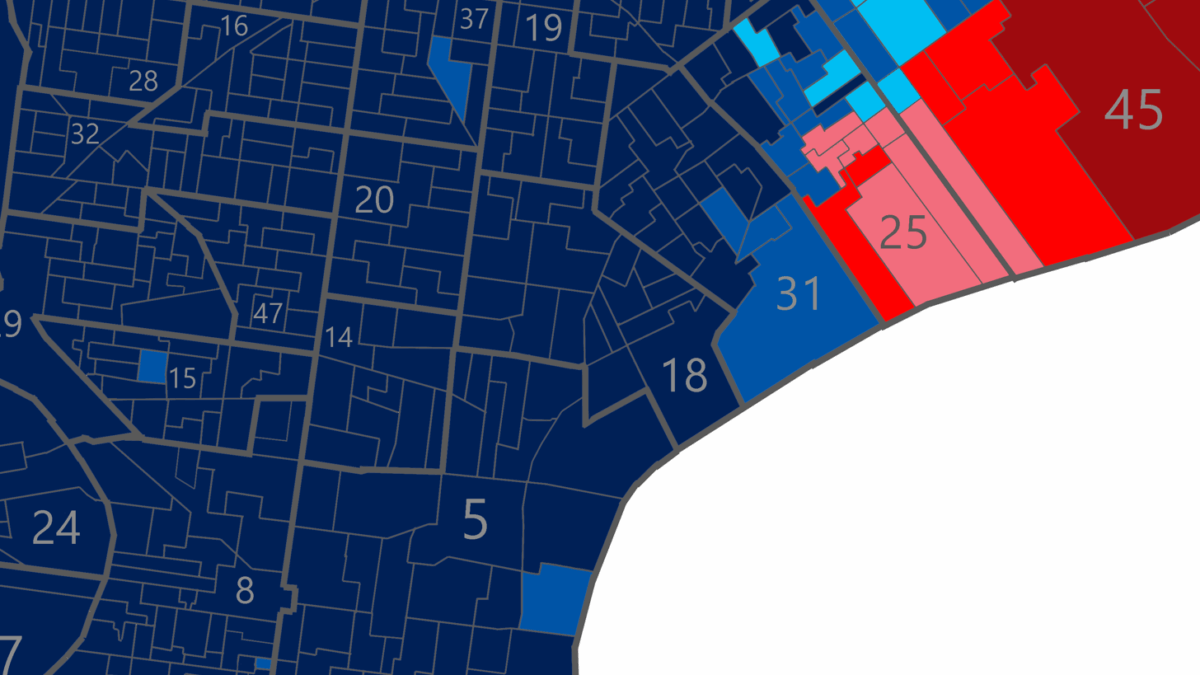

The compact would fundamentally shift presidential campaigns. Candidates would no longer visit Gettysburg, Martinsville, or any of the other small towns in Pennsylvania and the rest of the country, instead focusing their time on the largest population centers where they can leverage visits with policy proposals, advertising, and turnout operations. There are 43 million people in the New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago metropolitan areas, versus only 13 million in Pennsylvania—and it’s a lot easier to organize in Brooklyn than Lycoming County.

More important than the loss of campaign visits, however, would be the loss of attention to the issues and concerns of Pennsylvanians. If NPV were in effect, there would no longer be any need to care about the interests of Pittsburg’s steelworkers, nurses in Allentown, farmers in Lancaster County, or any other group that doesn’t form a large national voting-block.

If NPV were in effect, there would no longer be any need to care about the interests of Pittsburgh’s steelworkers, nurses in Allentown, farmers in Lancaster County…

The compact also suffers from numerous legal and political problems. It may violate the U.S. Constitution for a couple of reasons, including the fact that it increases the power of member states at the expense of others. It may also violate many state constitutions, nearly all of which (including Pennsylvania’s) require that a person be a resident of the state to vote in its elections–under the compact, of course, nonresidents have their votes counted for the state’s electors.

Even if the compact were constitutional, and even if the shift toward major metropolitan areas were desirable, the compact also suffers from the fact that it is a bundle of “electoral crises” (more on that term in a second) waiting to happen, plunging the nation into a political and legal catastrophe.

The biggest problem here is that there is not an official national vote count that could be used to conclusively determine a presidential winner. Every state conducts its own elections according to its own laws, with significant differences in how votes are cast, counted, and reported. Trying to aggregate vote totals across state lines would be a fiasco, at least in a close national election.

Under the compact, each state’s chief election official—the Secretary of State in Pennsylvania—is responsible for determining the vote totals of every nonmember state, and that official is supposed to rely on results provided by other states. But the results provided by other states aren’t always accurate—New York’s results reported on its Certificate of Ascertainment is habitually missing tens or even hundreds of thousands of votes. In 2012, New York left about 425,000 votes off its certificate.

There’s also the problem of Ranked Choice Voting (RCV). With RCV, voters rank candidates in order of preference: first, second, third, and so on. If no candidate receives a majority of first choices, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and voters who picked that candidate as their first choice will have their votes counted for their second choice. This process continues until one candidate has a majority.

The problem with NPV is that it expects states to report only a single vote total for every candidate. But with RCV, there can be two vote totals for each candidate—the initial count of first-place votes and the final count after the RCV process has transferred votes from lower-ranked candidates to higher-place candidates. Initial and final vote totals can differ by tens or even hundreds of thousands of votes—the winner in the recent New York City mayoral primary, for example, gained about 115,000 votes in the RCV process while the runner-up gained more than 210,000 votes.

There’s no clear answer to whether initial or final RCV numbers should be used, and the chief election officials of each member state could, in a close election, be in a position to decide the outcome based on which set of numbers they chose.

An even greater danger is that RCV could literally erase hundreds of thousands or even millions of very real votes for the Democratic or Republican candidate if they finish behind a third-party candidate in a state, which last happened in 1992. Had RCV been in place in Maine and Utah that year, almost 400,000 votes would have been completely erased for Bush and Clinton in the national vote totals.

Another major problem with NPV is that if official vote totals aren’t available from any state in time for the compact member states to use them (even if the state is complying with their own and federal laws regarding certification and reporting of votes), then the chief election officials in NPV states are free to “estimate”—that is, make up—vote totals for those states and use them to determine the winner. Even assuming that these officials all make good-faith efforts to arrive at a reasonable estimate, it’s an impossible task and would completely delegitimize the entire election.

Even assuming that these officials all make good-faith efforts to arrive at a reasonable estimate, it’s an impossible task and would completely delegitimize the entire election.

There are also no provisions for a recount in the compact. Because each state has its own laws on when recounts are triggered, in a close national election, some states might recount ballots while others do not, and some of those states conducting recounts might count the “hanging chads” while others don’t. Massive litigation would ensue, including over which provisional and late-arriving absentee ballots are to be counted.

These and other defects in the compact “raise the specter of electoral crises” according to Vikram David Amar, one of the law professors who initially helped develop the idea of the NPV compact. He’s called out what he sees as “dangerous gaps” in the compact, and, while he remains supportive, he is urging states that pass the compact to delay its effective date for at least a decade, which he hopes will give Congress time to resolve the many serious problems the compact creates.

The compact is bad for Pennsylvania, eliminating its unique voice in the presidential election process and giving voters in every other state the power to decide how its 19 electoral votes will be cast. It’s also bad for the country, pushing candidates to ignore all but the most populous parts of the country and risking a legal, political, and constitutional crisis as a result of its poor design. Pennsylvania should keep the power to select Pennsylvania’s electors in the state and not farm it out to the rest of the country.

Sean Parnell is Senior Legislative Director for Save Our States, an organization dedicated to defending the Electoral College.

Only people it would be bad for are extremist Republicans who’ve only won the popular vote ONCE in the last quarter century. Fact is, they’re terrified of what would happen if they actually had to go by the popular will of the American people to pick presidents.

Same reason they’re ok stomping on the founding principle of our nation “no taxation without representation” as long as it’s in a Democratic stronghold like DC. Republicans are terrified of being held directly accountable to the American people.

In the last quarter century there have been six presidential elections. The first of those, 2000, was the closest–Bush narrowly won the electoral vote while Gore received a slim popular vote plurality (but not a majority, just as Clinton did not receive a popular vote majority in either of his wins in the preceding two presidential elections). In 2004, Bush won reelection and received a slim popular vote majority. In 2008, Obama won what counts as a landslide in recent presidential elections, including a popular vote margin of 7%, and he won with about half that margin four years later.

Thanks to her strength in California, Hillary Clinton received more popular votes nationally in 2016 even as she lost the Electoral College. Just as Gore had lost because he failed to win states that Democrats had traditionally won, Clinton lost because she lost Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The irony of those elections is that it was the Democrats whose movement to the left stoked voter turnout on the costs–especially in California (Clinton’s margin there was over 4 million votes)–while alienating more moderate voters in places like the Rust Belt. Trump was rewarded for relatively moderate policies–borrowing from union Democrats–in those same states.