Ben Mannes: Trust without verification — Minnesota’s welfare fraud scandal exposes Philadelphia’s oversight gaps

Minnesota’s multibillion‑dollar Somali‑linked welfare fraud scandals, anchored by the Feeding Our Future case, were enabled by glaring failures of oversight that allowed shell nonprofits and pass‑through entities to siphon off public funds with minimal scrutiny. The same structural weaknesses — thin staffing, fragmented jurisdiction, and a growing reliance on lightly regulated nonprofits — are even more pronounced in larger, higher‑poverty cities like Philadelphia, where oversight capacity lags far behind the scale and complexity of public assistance spending.

Minnesota’s Feeding Our Future scandal exposed how what should have been a routine child nutrition program ballooned into a sprawling criminal enterprise.

A 2024 report from the Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor concluded that the Department of Education’s “actions and inactions created opportunities for fraud,” citing failure to act on warning signs even as reimbursements surged.

- The department eased off enforcement after the nonprofit sued and accused officials of racial discrimination, and the auditor found that fear of legal and media backlash influenced regulatory decisions.

- State and federal investigators later alleged that conspirators stole hundreds of millions of dollars by submitting fake meal counts, fabricated child rosters, and sham invoices for food that was never purchased or served.

The scandal was not limited to one nonprofit but revealed systemic gaps in basic controls — such as verifying attendance, monitoring vendor relationships, and cross‑checking claims — that allowed fraud to flourish for years before law enforcement intervened.

A key feature of the Minnesota schemes was the use of nonprofit organizations, religious entities, and nominal community centers as the primary billing vehicles for federal nutrition money. Conspirators stood up or repurposed nonprofits that appeared legitimate, but were used to channel claims through a sponsoring nonprofit like Feeding Our Future, which itself acted as an intermediary between local sites and the state agency.

- Federal indictments describe nonprofits applying to become official food sites, then submitting false rosters and invoices while using the proceeds for luxury goods, real estate, and overseas transfers rather than meals for children.

- Because these entities straddled the line between public funding and private incorporation, they often fell into blind spots where local controllers and inspectors general had limited authority to conduct regular audits, especially once federal dollars were routed through layers of contractors and subgrantees.

This structure mirrors a broader trend in social policy: instead of building new brick‑and‑mortar public agencies, governments increasingly outsource core welfare functions to nonprofit or quasi‑private providers, which can sit just outside the day‑to‑day audit and investigative reach of traditional city watchdogs.

Why big cities like Philadelphia are exposed

New York City, with more than 12,000 employees at its Human Resources Administration with a dedicated Bureau of Fraud Investigations with hundreds of special investigators supported by the city’s fully-sworn Department of Investigation, handling thousands of public benefit cases a year, has built a relatively extensive in‑house anti‑fraud infrastructure. Yet even there, recent oversight reports have documented vulnerabilities in newer housing and assistance initiatives when staff were inadequately trained and monitoring did not keep up with program growth.

Philadelphia, by contrast, relies heavily on the Pennsylvania Office of State Inspector General (OSIG) for welfare fraud investigations, rather than a large, city‑based oversight force. OSIG’s statewide mandate covers SNAP, cash assistance, and other programs, and publicly available materials highlight individual trafficking and overpayment cases, but they also underscore that a centralized office with roughly a few hundred employees is responsible for policing fraud across dozens of counties and billions in assistance.

- Pennsylvania officials tout aggressive SNAP trafficking prosecutions, yet the caseload shows that investigators are often tied up chasing individual retailers and recipients rather than auditing complex nonprofit networks and sophisticated grant‑funding structures.

- In a city as big and as poor as Philadelphia, the volume of public assistance flowing through local nonprofits, homecare agencies, and contracted providers far exceeds what a thin state inspector general staff can routinely inspect on the ground, creating the same kind of vacuum Minnesota experienced in practice.

The result is an asymmetry: New York City can field hundreds of dedicated investigators inside its welfare bureaucracy, while Philadelphia leans on a comparatively small, overstretched state office that must triage cases statewide, making it far more likely that large‑scale fraud in complex public-private arrangements goes undetected for years.

Recent audits and investigations show that the most vulnerable programs are those built on trust‑and‑attestation models rather than intensive, routine inspection. Minnesota’s Child Care Assistance Program audit found that about eleven percent of sampled payments had attendance documentation flaws — missing records, inaccurate dates, or billing for children who were absent — prompting federal officials to warn that limited oversight “could increase the risk of fraud, waste, and abuse.”

Homecare, universal or subsidized pre‑K, recovery housing, and childcare subsidies in cities like Philadelphia follow similar patterns:

- Homecare programs often reimburse agencies and individual caregivers based on timesheets or electronic visit verification that can be manipulated when on‑site checks are rare and medical necessity reviews are cursory.

- Pre‑K and childcare initiatives rely on provider‑submitted enrollment and attendance figures; when documentation is not matched against independent data and surprise inspections are infrequent, inflated rosters and ghost children become low‑risk, high‑payoff fraud schemes.

- Recovery houses and supportive housing funded with public dollars present additional risks when operators self‑report occupancy, services, and compliance, but local inspectors lack staff to conduct regular unannounced visits and rigorous financial audits.

In each case, policymakers designed programs to move money quickly and flexibly through community‑based providers, assuming good faith and building only light compliance infrastructure, which creates fertile ground for networks willing to fabricate paperwork at scale.

Lessons for Philadelphia

The Minnesota scandals demonstrate that sophisticated fraud does not require hacking complex systems; it only requires exploiting the distance between funders and service sites in environments where oversight is reactive, fragmented, and easily chilled by political or legal pressure. Philadelphia’s combination of high need, heavy reliance on nonprofit and public‑private delivery models, and dependence on a relatively small, state‑run inspector general’s office means the city is structurally at least as exposed as Minneapolis was before the Feeding Our Future case broke—and potentially more so, given its scale and concentration of poverty.

Unless cities like Philadelphia invest in their own specialized welfare fraud units, demand transparent data‑sharing from nonprofit contractors, and mandate routine audits and surprise inspections of trust‑based programs, there is every reason to expect that the abuses uncovered in Minnesota are not an outlier but a preview of larger scandals waiting to surface in bigger metropolitan areas.

Based in Philadelphia, A. Benjamin Mannes is a consultant and subject matter expert in security and criminal justice reform based on his own experiences on both sides of the criminal justice system. He is a corporate compliance executive who has served as a federal and municipal law enforcement officer, and as the former Director, Office of Investigations with the American Board of Internal Medicine. @PublicSafetySME

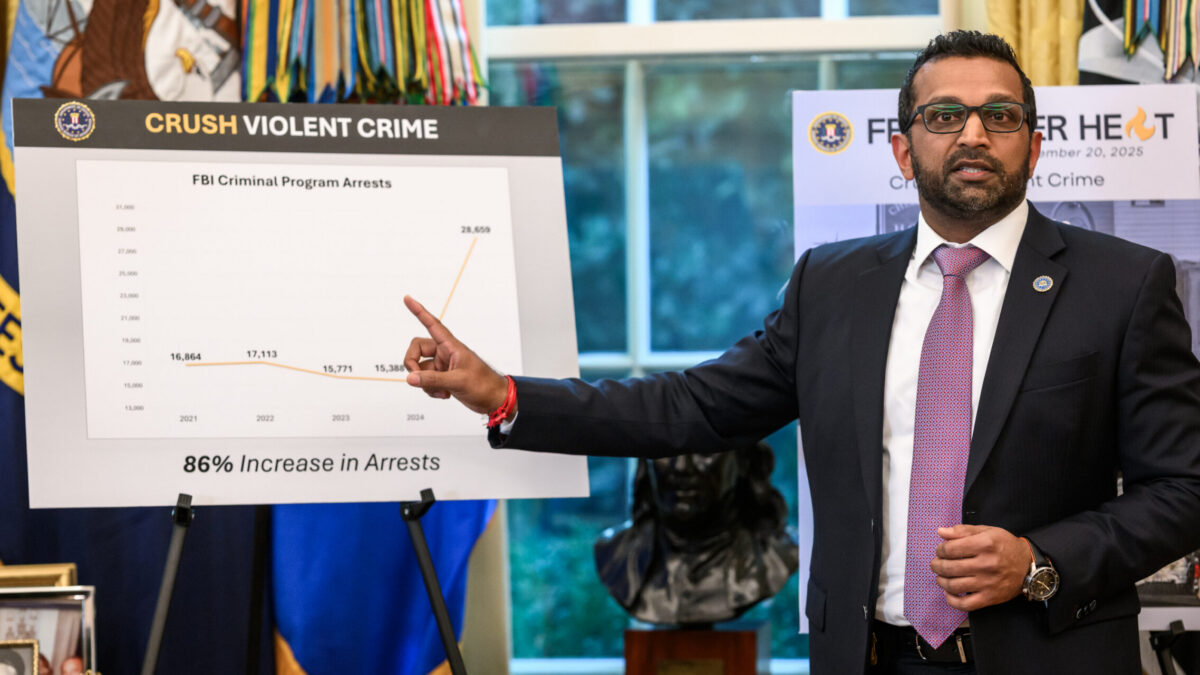

Tuesday (1/6/26) the Transportation Security Administration reported that it detected and flagged nearly $700 million in cash moved in luggage out of the Minneapolis airport by Somali couriers in 2024 and 2025 alone.

Minneapolis travelers alone had $342.37 million in their luggage in 2024 and $349.4 million in 2025, and the totals nationwide are likely to be much higher, the TSA officials stated.

They knew this because it was all reported on the required forms when you have large amounts of cash in luggage. This shows that only now are the disjointed departments in government are starting to compare notes to see just how much of the taxpayers’ money is actually being misused/stolen.

And who seriously thinks the voter rolls are accurate? I renewed my license this year and the organ donor and voter registration questions were confusing; because it seems they are intentionally designed that way. These systems seemed designed to allow fraud.

It is alarming to see so many nonprofits and NGOs being hired to do the work the state agencies are supposed to do themselves. How can an agency know what is going on with their client group when they are “hands off” administrators? It is my opinion the reason there are so many nonagency providers employed is not laziness by the agencies but in a more sinister vein, because nonprofits and NGOs operate with little to no oversight. This makes them ideal vehicles for politicians to use to reward supporters and buy votes, fraudulently or not.