Willie, Mickey, and the Duke — and perhaps Richie

Every baseball fan knows the song “Willie, Mickey, and the Duke” about the three great Big Apple sluggers of the 1950s. It heralds their feats during one of the great eras of New York city baseball, a time when the Dodgers, Yanks and Giants led by Duke Snider, Mickey Mantle, and Willie Mays won fourteen pennants and seven World Series.

There is no doubt that these three put up some impressive offensive statistics during the decade. Mays and Mantle won three MVP awards between them while Snider helped lead the Dodgers to win five pennants and one World Series.

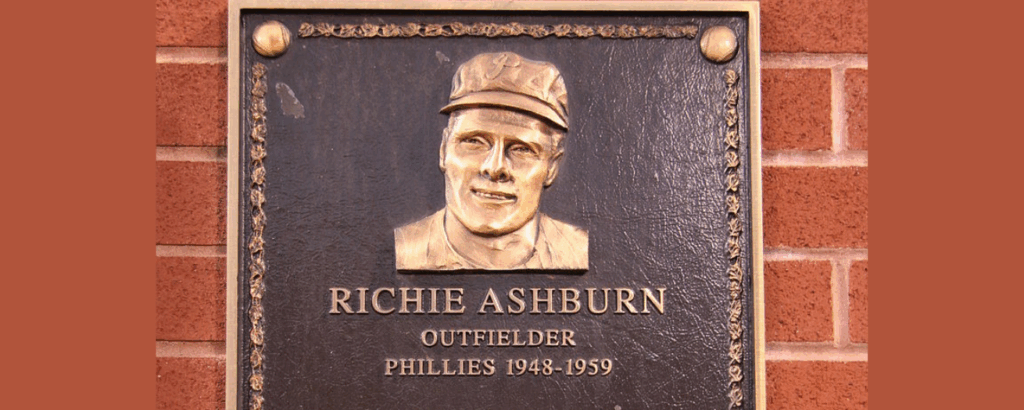

But this New York ditty, so typical of New York boosterism, hides one fact: there was an equally talented centerfielder playing one hundred miles to the south in Philadelphia. Richie Ashburn had a pretty good decade himself. As they say, let’s look at the record: Ashburn won two batting titles and compiled more hits during the decade of the ‘50s than any other major leaguer and that includes such Hall of Famers as Willie, Mickey and the Duke as well as Stan Musial, Hank Aaron or Ted Williams.

Pretty good company

With regard to lifetime stats, Ashburn was no slouch — he had a higher lifetime batting average than the Big Apple trio and had more career hits than Snider or Mantle. As a centerfielder despite all the praise for the Big Three, Ashburn posted superior numbers. It was argued that he didn’t have a strong arm — he always said he only had to make one throw: the one that nabbed Dodger runner Cal Abrams at home and gave the Phillies a chance to win the pennant in 1950. Actually, Ashburn’s arm was pretty strong: He led all outfielders in assists three times in the 50’s. Mantle and Mays did it once each.

Even more dramatically, Ashburn dominated in putouts, a sign of an outfielder’s range, vital for a centerfielder in particular. Only eight times has an outfielder reached 500 putouts in a season — Ashburn accounted for four of them.

None of this means that Ashburn was a better or more valuable player than “Willie, Mickey, or the Duke.” Any knowledgeable baseball fan would certainly choose Mays or Mantle ahead of Ashburn as a more valuable player to have on your team — the case for Snider is less clear. Mays is perhaps the best all-around player — offensively and defensively — in the last three quarters of a century. He was certainly the best I ever saw during my seventy years of watching (and writing about) baseball.

But it is simply the case that outside of Philadelphia, Ashburn is largely forgotten today.

An interesting aspect of the whole discussion is the careers of the Big Apple trio’s post-baseball careers. Willie, Mickey, and Duke all struggled after they retired and never found a place for themselves after their playing days were done. None became managers nor did they stay in baseball as coaches or in any executive capacity. In fact, the three of them had problems adjusting to life after baseball. Snider got caught by the IRS for not reporting money earned for signing autographs at Baseball Card Shows.

Mantle’s post-baseball life was sad. He had started drinking during his career and continued afterwards. Aside from Old Timer games at Yankee Stadium he had little contact with the game he played so brilliantly.

Willie Mays’ move to San Francisco took him out of the city that loved him so much. For some reason the San Francisco fans never warmed up to him the way the fans and writers of the Big Apple had. If he had stayed in New York, he would have been lionized by the media the way Joe DiMaggio had been — a cherished idol. It took the last years of his life and his death for San Francisco to recognize what a treasure they had.

Ashburn had the best post playing career of the great centerfielders of the ‘50s. After ending his playing days hitting .300 and not embarrassing himself by staying too long, he joined the Phillies broadcasting team. Schooled by announcers like Bill Campbell and especially Harry Kalas, Ashburn became an immensely popular color commentator, famous for witticism and often outrageous comments. Asked by Kalas once if he had a favorite bat, Ashburn said yes, he even slept with some old bats. Long after Willie, Mickey, and the Duke made it to the Hall of Fame, Ashburn got his place there, sadly just two years before his death.

So let’s change the tune: Willie, Mickey and Duke and that white haired guy in Philly.

John P. Rossi, Professor Emeritus of History, La Salle University