Howard Lurie: Under whose jurisdiction? The Supreme Court’s next big constitutional test

One of the cases yet to be decided by the Supreme Court this term involves the constitutionality of “birthright citizenship.” Birthright citizenship is the principle that anyone born in the United States is a citizen of the US regardless of the status of the child’s parents. Advocates of birthright citizenship argue that it is a legal principle enshrined in the US Constitution. Others, including President Trump, argue otherwise.

The basis for the argument is Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution which says that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Shortly after taking office, President Trump issued an Executive Order against birthright citizenship. A number of challenges were brought, and several federal judges ruled against him issuing nationwide injunctions halting enforcement of his Order.

What the SCOTUS will decide, however, is unknown. What can be said with a certain level of confidence is that, regardless of what the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended and wrote, whatever the Court says will be the law of the land.

Opponents of the birthright citizenship argument, including this writer, argue that advocates of birthright citizenship completely ignore the language of the provision that requires the person born in the US also be subject to the jurisdiction of the US. That language clearly recognizes that not all persons born in the US are subject to the jurisdiction of the US. No one disputes that children born to foreign diplomats are not subject to the jurisdiction of the US.

Proponents of the birthright citizenship argument not only ignore the conjunction “and” that precedes the “subject to the jurisdiction” provision, but they also ignore a second “and” that precedes “of the State wherein they reside.” In what State does the child born in the United States to a foreign visitor reside? Proponents of the birthright citizenship argument assert that such a child is still a citizen of the United States. Obviously, that child is not a resident of any State.

Yet the citizenship conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment is not just US citizenship, but also State citizenship. The proponents of the birthright citizenship argument are necessarily claiming that one can be a US citizen without being a citizen of a State. To them residency is irrelevant, despite a clear objective of the Fourteenth Amendment provision to confer State citizenship.

It is probably beyond dispute that the major purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to make former slaves US citizens, and to deny to the former slave States the ability to legally deny citizenship to them. The Amendment also guaranteed “equal protection” to the former slaves. It is doubtful that any thought was given to the status of children born to parents who had entered the US unlawfully. And, but for the recent incursion of thousands of illegally entering migrants, it is doubtful that the present controversy over birthright citizenship would have arisen. In all likelihood the small number of children born to illegal entrants before the current situation would have been treated as citizens.

However, with literally millions of undocumented immigrants living in the US, the consequences of making their children US citizens has significant political impact. That may well explain why the issue is currently receiving so much attention.

Proponents of the birthright citizenship argument claim that past decisions of the Supreme Court support their claim. And there is some validity to this argument. However, as we all know, changes in prevailing attitudes sometimes allow the Court to overrule prior precedents. Racial segregation in public schools is, perhaps, the most well known example. “Separate but equal” was the law of the land for many years. It did not take a Constitutional amendment to change that.

Congress, of course, could constitutionally enact birthright citizenship. And, unless the Supreme Court rules that it is constitutionally mandated, Congress could limit it. It is unfortunate that Congress has allowed the situation to reach the Supreme Court when they could have resolved it through legislation. Nowhere in the Constitution is there any guidance as to what subjects someone to US jurisdiction. Native Americans were not considered US citizens following the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification. It was not until 1924 that Congress and the President made them citizens in the Indian Citizenship Act.

Proponents of birthright citizenship would have us believe that prior to June 2, 1924, a child born in the United States to a foreign tourist was a US citizen, but a child born in the United States to a Native American was not.

There are nations that do confer birthright citizenship on children born on their territory, and there are nations that do not. In each case there is usually a rationale for the policy being followed. I’ve not heard any rationale offered by proponents of birthright citizenship for it in the United States. All they offer is a distorted reading of the language of the amendment. Constitutional arguments should have more support than that.

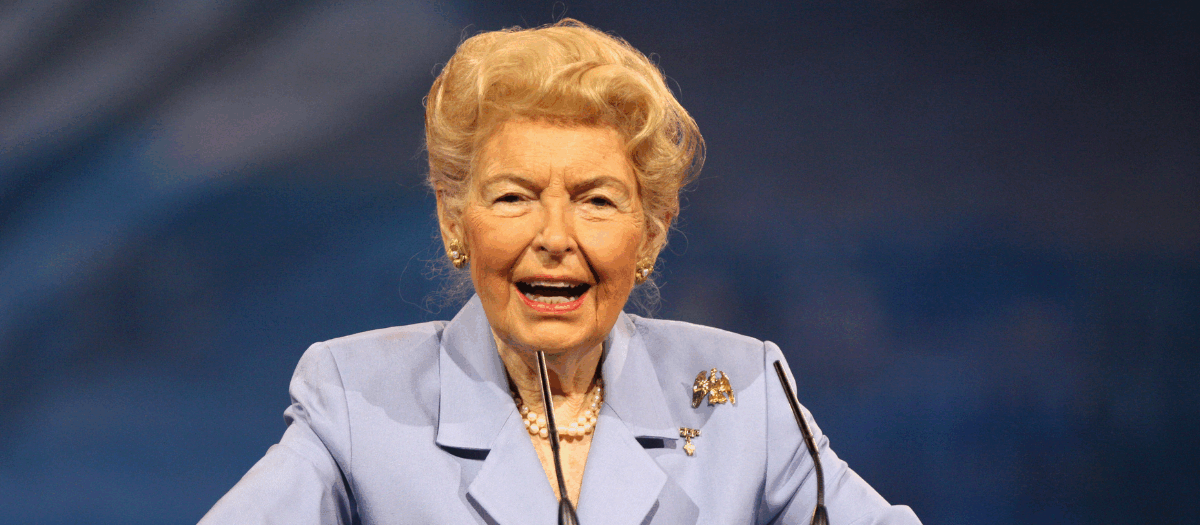

Howard Lurie is Emeritus Professor of Law, Charles Widger School of Law, Villanova University